The Smelter Debate

California regulators have invited public comment on a long-awaited draft permit for the state’s only lead battery recycling facility. Residents near the Ecobat smelter in Los Angeles County have complained for years about uneven regulatory oversight and legacy lead pollution at the plant. This series examines key aspects of the permit and the permitting process.

Twenty years ago, it was legal for the battery recycling facility in the City of Industry to spew hundreds of pounds of lead a year into the air.

A health hazard assessment in 2000 found that the smelter’s releases of lead, arsenic, benzene and a process additive called 1,3-butadiene raised the risk of cancer in surrounding neighborhoods more than any other facility in Los Angeles County.

Then federal law tightened safety standards for airborne lead.

In 2008 the facility, then owned by Quemetco and now by Ecobat, installed pollution-control equipment that uses an electric charge to capture particulate pollution and wash it away. The amount of lead the companies reported releasing from the smelter’s stacks dropped dramatically, from as much as 704 pounds in 2003 to 5 pounds in 2022, well within regulatory limits.

That has not reassured many people who live nearby, some just 600 feet away. Studies show no amount of lead is safe, and sometimes Ecobat has released more pollution than regulators allow per day, hour or month.

In April 2019, for example, the facility allowed discharges of lead and arsenic to rise above 30-day limits. A release of arsenic in 2018 exceeded 24-hour limits, as did a release of arsenic and lead in 2017, according to air regulatory records and a 2024 compliance-history memo by the Department of Toxic Substances Control, or DTSC. To settle violation notices in 2020 and 2021, including one specific to smelters in 2020, Ecobat agreed to pay a $35,000 fine to air regulators in 2022.

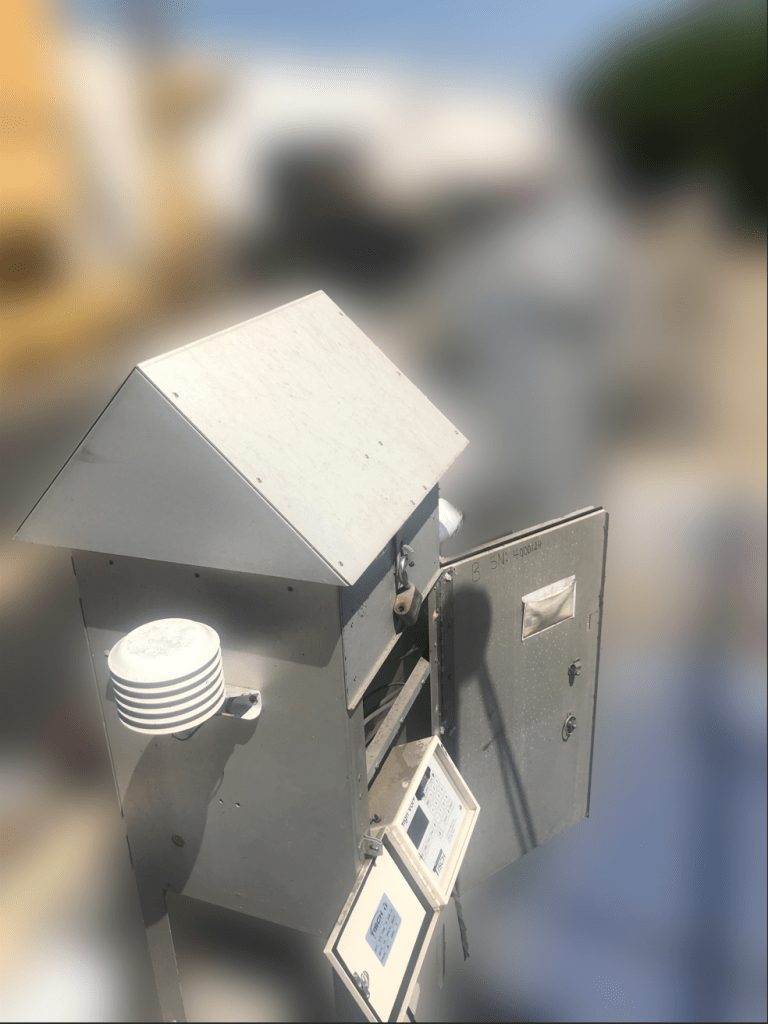

In July this year, DTSC released a draft permit for Ecobat that would require the company to pay for expanded air and soil monitoring, including by installing for the first time an air monitor in a nearby neighborhood. (Four existing air monitors are at the fenceline.) Ecobat also would have to tell residents about regulators’ findings and data more often.

“We have more stringent requirements about what they need to notify us about, if there are any releases,” said DTSC Director Meredith Williams, who is stepping down at the end of September. “And more transparency, making sure that monitoring data are available to the public.”

But it’s not clear whether more monitoring and transparency would protect the public.

Detection Beyond the Fence

The new air monitor would measure 24-hour average concentrations of lead and arsenic in Avocado Heights, an unincorporated neighborhood in the San Gabriel Valley that is downwind of the facility. Under the permit’s terms, Ecobat would propose at least three locations for the equipment; the company said the locations likely would be “largely determined by where Ecobat can find a property owner willing to give us access to their property to install the monitor in a secure location.” DTSC would have final say.

But if the neighborhood air monitor detects excess lead or other toxins, the permit doesn’t set any penalties. And while DTSC oversees hazardous waste laws, it usually defers to a regional agency that enforces air-pollution laws. That agency, the South Coast Air Quality Management District, already has a smelter-specific rule that sets monthly air pollution limits. At Ecobat, those are enforced using the four fenceline monitors.

Nahal Moghrabi, a South Coast spokeswoman, said in an email that ”DTSC did not coordinate with South Coast AQMD on this air monitoring requirement.”

The new monitor would be “outside the scope” of air regulators’ smelter rule, Moghrabi wrote. When fenceline monitors detect lead that exceeds local standards, the facility may be written up by air regulators and face penalties. But if that happened at the neighborhood monitor, Moghrabi wrote only that “South Coast AQMD would investigate the situation which could lead to additional ambient monitoring.” She did not mention penalties.

DTSC’s Katie Butler, deputy director for the state’s hazardous waste management program, said South Coast’s response is “surprising,” and that she and her department “need to make sure we stay coordinated with South Coast on this condition and the development of the plan.” She said that elevated levels of lead or other toxins “could prompt a deeper investigation,” but stopped short of saying that pollution could prompt penalties. DTSC would work closely with the South Coast air district, she added.

The neighborhood monitor’s key function, Butler stressed, is to “ground truth” what neighbors know about their risk from Ecobat’s operations. Specifically, she said, the monitor would improve the public’s understanding of a health hazard assessment, also recently released, finding an elevated cancer risk for 9 out of every million residents in the surrounding area.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guidance deems cancer risk levels acceptable when they’re elevated for between 1 and a million and 1 in 10,000 people near Superfund sites.

“It’s almost right in the middle,” Butler said. “When you fall in that range, it signals the need for either more monitoring or mitigation. This is also where we consider the existing vulnerabilities of the community.”

Ecobat is not a Superfund site, and it’s not clear why DTSC is applying the EPA’s guidance for such sites as a standard for action.

“In developing this condition, we were being responsive to some of the things we heard from the community members over this last year,” Butler said.

Ecobat is considered a major source of pollution under the federal Clean Air Act, which is why South Coast oversees its federal and state requirements for controls and monitors at its stacks. The air district added the regional smelter rule 14 years ago, when Exide, another lead battery recycler south of downtown Los Angeles, was struggling to control its air pollution. Exide shut its doors and eventually declared bankruptcy. It never added new pollution control equipment like Ecobat did.

Neighbors of Ecobat say air quality remains a concern because even after its upgrades, Ecobat has violated, or been accused of violating, air regulations dozens of times. Since 2009, South Coast has issued Ecobat 22 notices of violation and another 20 “fix-it tickets” for federal or local rules, DTSC’s compliance report shows. (A notice of violation is essentially an allegation that triggers an investigation.) Many were disputed; the process can take months or years to finalize. Since 2019, Ecobat has been accused of violating the smelter-specific local rule four times, including by failing to maintain building pressure to keep emissions inside and to notify regulators about problems.

DTSC’s draft permit takes the record of violations into account, noting in a fact sheet that Ecobat “has periodically had unplanned shutdowns of its emissions control devices.” The company says the incidents when pollution was released were generally minimal. In regulatory filings, Ecobat has blamed air pollution releases from 5 to 7 years ago on an outside truck, an external power outage or contractor maintenance activities.

A Demand for Facts

In addition to creating more air monitoring data, DTSC’s draft permit would add requirements for Ecobat to disclose it, along with other data already gathered at the fenceline and the stacks. (South Coast requires Ecobat to publish summarized fenceline air data now.)

The draft permit would demand several disclosures. Among them: notifying regulators within an hour after an unplanned shutdown, and holding regular community meetings, at which it must report monitoring results and new complaints and violation notices.

But even if Ecobat publicly disclosed more information, it wouldn’t solve an underlying frustration complicated by the messy layer cake of overlapping regulators. Investigating and writing up facilities in California can take months or years, and regulators may offer scant information during that time.

What has happened since one incident in June 2023 illustrates the problem. At that time, air regulators alleged Ecobat failed to collect 24-hour monitoring data at the fenceline. But South Coast didn’t make that public until February this year, when the district issued a notice of violation containing little more than the date, location and legal standard in question. Moghrabi, of South Coast, says the district is unlikely to resolve the case or release more information before comment closes on the DTSC draft permit in November.

Katie Butler, who will take over as DTSC director in October, said that while South Coast is the lead authority on air pollution, the draft permit’s new provisions have value. “This is us at DTSC, utilizing the full extent of our authority in the permitting space to augment that data and information, for not just the community members but also regulators to use.”