In the spring of 1977, federal workplace-safety regulators were confronted with a grim government study. Current and former employees of two Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. plants in Ohio had been using benzene, a chemical long suspected of causing leukemia, to make a rubberized food wrap called Pliofilm. Workers who had been exposed to benzene in concentrations once considered safe had a five- to 10-times higher risk of developing leukemia than the general public, the study found.

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, concluded that the legal limit at the time — 10 parts per million, or 10 ppm, over an eight-hour workday — was far too lenient. Led by Eula Bingham, a plain-spoken Kentuckian appointed by Jimmy Carter, the agency issued an emergency temporary standard that limited exposure to 1 ppm.

What happened next marked the beginning of a battle over benzene regulation that continues to this day. The more the chemical is studied, the worse it looks, with recent science tying even miniscule amounts to childhood leukemia, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and other cancers. Industry, however, says benzene is harmful only in high doses and causes only a few specific malignancies.

A Public Health Watch review of corporate documents unearthed in lawsuits, and interviews with scientists, lawyers and other experts, show a pattern of industry deception and denial on a chemical that has inflicted misery for more than a century. In one previously unpublicized incident, for example, Shell Oil Co. failed to report a string of cancer deaths within its workforce that could have foreshadowed benzene’s destructive capabilities.

To some extent, these tactics have worked. The occupational exposure limit for benzene remains 1 ppm. There is still no federal standard for the chemical in ambient air — defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as “that portion of the atmosphere, external to buildings, to which the general public has access.” As a result, people who live in industrialized communities, including some in eastern Harris County, Texas, can inhale heavy doses of the carcinogen.

The American Petroleum Institute, or API, challenged Bingham’s temporary benzene standard so quickly in 1977 that it never took effect. When OSHA proposed making 1 ppm the permanent workplace limit a year later, the trade group bottled up the rule in court for nearly a decade. Two researchers later estimated that the delay would result in “between 30 and 490 excess leukemia deaths.” They added that “deaths from aplastic anemia and lymphoma” — a rare blood disorder and a blood cancer — “will likely add to this toll.”

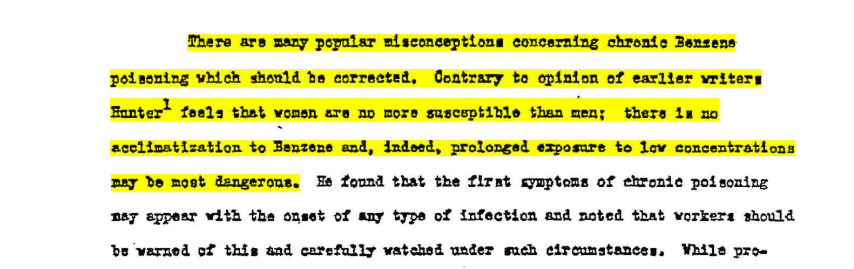

Internal documents show that oil and petrochemical companies — prodigious users and emitters of benzene — knew about the chemical’s toxicity even as they protested the OSHA standard. In a confidential 1943 report to Shell Development Co., for example, Dr. Mayo Soley of the University of California Medical School summarized scientific literature indicating “there is no acclimatization to Benzene and, indeed, prolonged exposure to low concentrations may be most dangerous.”

In public, however, the companies and their trade groups produced their own studies to counter growing government concern.

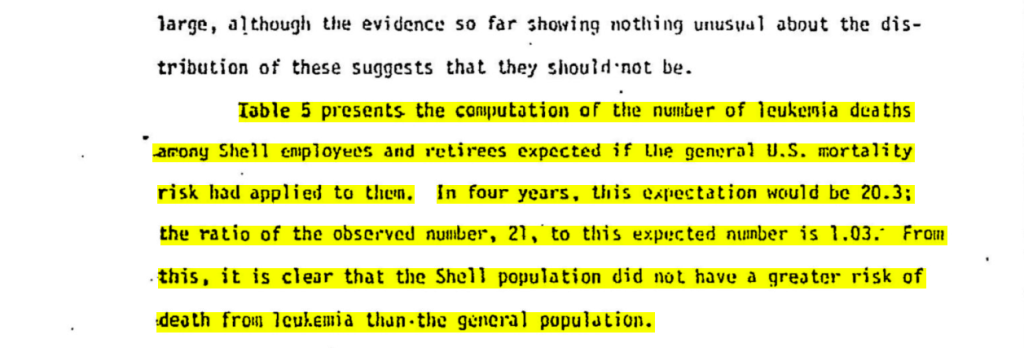

At a 1977 U.S. Department of Labor hearing, Shell presented findings of a study that examined the deaths of some 36,000 Shell workers and retirees. Conducted by Dr. Roy Joyner, then the company’s medical director, and Dr. Reuel Stallones, then dean of the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston, the study found that Shell’s employees “did not have a greater risk from leukemia than the general population.” Joyner and Stallones found 21 leukemia deaths among the men. The “expected” number in society-at-large, they reported, was 20.3.

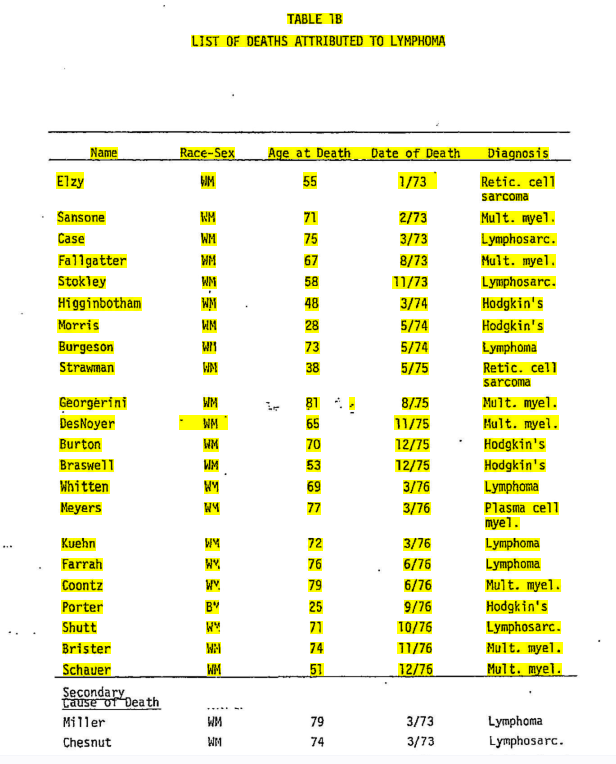

But the report Shell presented to the Labor Department had been cleansed of some crucial information. According to a draft of the report obtained by a lawyer decades later and made public for the first time here by Public Health Watch, an additional 22 workers had died from various forms of lymphoma, including multiple myeloma and reticular cell sarcoma, during the three-year study period.

Had Shell’s lymphoma findings been aired, they would have provided early warning of a truth now widely accepted by scientists but often refuted by defendants in lawsuits: that benzene can cause blood cancers other than leukemia.

“If I had been running OSHA at the time, I would have been furious,” David Michaels, an epidemiologist who led the agency from 2009 to 2017, said after Public Health Watch told him about the Shell episode. “For OSHA to be able to set a standard, it needs to understand all the potential health effects of exposure [to a chemical]. Not sharing that information with OSHA is really unethical and endangers the health of workers.”

A ‘Growing Menace’

Benzene is a hydrocarbon; its structure is a hexagonal ring of six carbon atoms, each with a hydrogen atom attached. It was discovered in 1825 by the English chemist Michael Faraday, who detected the chemical as a byproduct in the making of illuminating gas for lamps and streetlights. In 1845, a German chemist isolated benzene from coal tar, and four years later it went into industrial production.

In the 20th century benzene would be used to decaffeinate coffee (no longer) and in the production of paint-strippers and rubber cements. Today it’s used mostly to manufacture other chemicals, such as ethylbenzene, a precursor to styrene, an ingredient in rubber, plastics, insulation, auto parts and other products.

These people flat-out lied to the regulators.

Eric Williams, a lawyer in Metairie, Louisiana, referring to shell oil co.’s withholding data on cancer deaths in its workforce.

Benzene’s health effects became evident in the late 19th century, when researchers in Sweden and France identified the chemical as a bone-marrow poison. Nine young Swedish women who made bicycle tires developed aplastic anemia, which occurs when one’s marrow can’t make enough new blood cells. A young man in France began hemorrhaging after he was exposed to benzene in a dry-cleaning operation.

In 1922, physician Alice Hamilton, the first woman to be appointed to the faculty at Harvard Medical School, warned of the “growing menace” of benzene poisoning among American workers. Six years later, the first human case of leukemia linked to occupational benzene exposure was reported in the scientific literature.

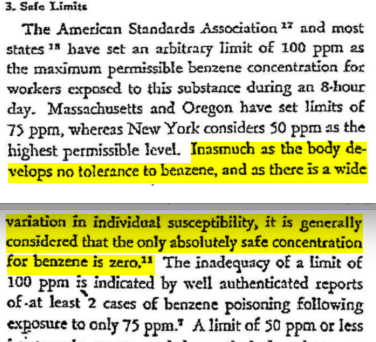

In 1948, a toxicological review prepared for the American Petroleum Institute by the Harvard School of Public Health concluded that “the only absolutely safe concentration for benzene is zero.” That stark admonition had little, if any, effect, and in 1951, Robert Kehoe, director of the University of Cincinnati’s Kettering Laboratory, had stern words for the API’s Medical Advisory Committee. The lab was overseeing an epidemiological study of oil-industry workers that would be abandoned years later due to lack of participation by the companies. It already had tested various hydrocarbons on animals and produced cancers.

“Certainly it is the height of futility, and a mere gesture of piety, to issue warnings and general instructions to employees of the industry, with the idea that absolution has been obtained thereby from responsibility for what may occur,” Kehoe wrote in a memo to the committee. Industry leaders should be concerned “not with the avoidance of moral or economic liability or responsibility, if and when occupational disease should develop, but rather with the prevention of such disease …,” he wrote.

Kehoe’s advice went unheeded, even as scientific evidence against benzene accumulated.

In 1973, Roy Joyner, Shell’s medical director, suggested in a memo that the company conduct medical surveillance on benzene-exposed workers. He noted that inhalation of “lower concentrations over a long period of time can produce chronic poisoning, affecting the blood and bone marrow and resulting in anemia, leukopenia [low white blood cell count], thrombocytopenia [low blood platelet count] and leukemia.”

A few years later, the Pliofilm study in Ohio intensified the debate over the chemical.

In August of 1976, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, or NIOSH, said the study offered “conclusive” proof that benzene caused leukemia. In October it urged OSHA to adopt an emergency temporary standard of 1 ppm. Not long afterward, Joyner and UT’s Stallones began their mortality study of Shell employees and retirees.

David Rosner, director of Columbia University’s Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health, found it unsurprising that Shell sought out UT as a partner.

“This was when the government was really trying to regulate industrial production,” Rosner told Public Health Watch. “It just seems part and parcel of that moment — when these companies are under deep suspicion, being identified as the culprits in workers’ deaths and environmental pollution — that they’d be willing to manipulate legitimate institutions.”

Joyner was asked in a 2009 deposition why he had chosen Stallones as his collaborator. “We wanted to have … an outside epidemiologist of good reputation so … our findings could be presented as objective,” Joyner said.

He played down Shell’s withholding of the lymphoma data in 1977, saying that the Labor Department hearings focused on “the relationship between benzene exposure and leukemia. At that point, to my knowledge, there was no such allegation regarding lymphoma.”

Stallones died in 1986, Joyner in 2018.

Peter Infante, an epidemiologist who worked on the Pliofilm study for NIOSH and later joined OSHA, called Joyner’s reasoning “totally absurd.”

“It’s very disappointing, in terms of public health and the prevention of cancer, that they did not present all of the data they had available to them,” Infante said. OSHA would have been interested in any blood cancers, he said.

Years later Infante analyzed the lymphoma statistics in Shell’s draft study and found a more-than-twofold elevation in risk of death. The excess was statistically significant, he concluded, meaning it was unlikely to be due to chance.

“These people flat-out lied to the regulators,” said Eric Williams, a lawyer in Metairie, Louisiana, who obtained the draft during discovery in a lawsuit against Shell. “It’s very obvious that somebody made a decision not to turn in these blood cancers to OSHA as required.”

During his 24-year career at OSHA, Infante sparred regularly with industry representatives over benzene.

In 1984, he accused Shell of withholding data on worker blood abnormalities at its refinery in Wood River, Illinois. Shell insisted there was no such data. Infante, who’d been contacted by a Wood River employee suffering from such an abnormality, knew there was.

When Infante pressed the issue, Shell’s industrial hygiene manager complained to Thorne Auchter, the head of OSHA under Ronald Reagan, that Infante was harassing the company and had put an “unnecessary strain” on its relationship with OSHA.

Shell eventually produced the data it had said didn’t exist.

“Industry never wants to provide you with data, or they fabricate data so no one has to change any regulations,” said Infante, who retired from OSHA in 2002 to consult for plaintiffs in toxic-exposure cases.

Shell representatives did not respond to requests for comment from Public Health Watch.

A spokeswoman for what is now known as the UTHealth Houston School of Public Health said the university would have no comment on Stallones’ participation in the 1977 Shell study. Nor would she respond to a question about how UT ensures that its science is unbiased, given the tens of millions of dollars it has received from the oil, gas and petrochemical industries over the years.

State records show that Shell alone has donated more than $53 million to UT since 1980 for sponsored research. This total does not include Shell donations unrelated to research, disclosure of which is forbidden under state law, the university says.

Industry Pushback

The API’s challenge of the 1978 OSHA benzene standard made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In a 5-to-4 decision, the court held in 1980 that OSHA hadn’t justified tightening the exposure limit from 10 ppm to 1 ppm.

OSHA started over and reissued the standard in 1987. But by then OSHA knew its new rule was flawed.

A year earlier, NIOSH had recommended that the workplace limit be set at 0.1 ppm, or 10 times lower than the new standard. OSHA’s own risk assessment showed that the 1-ppm limit would likely result in 10 excess leukemia deaths per 1,000 workers — a number 10 times higher than OSHA’s usual target of one excess death per thousand.

The agency’s concerns also extended to other blood cancers. “Epidemiologic studies of workers exposed to benzene have demonstrated significant excesses of leukemia, multiple myeloma, and lymphatic cancers as well as chromosomal aberrations,” the 1987 rule stated.

“What you have is an industry that knows it’s going to lose profitability if the true extent of benzene’s health hazards is recognized. It would cost them a lot of money to take benzene out of gasoline and other products.”

Andrew DuPont, a Philadelphia lawyer who represents plaintiffs in benzene-exposure lawsuits

Fearful that stricter occupational and environmental limits — and lawsuits from cancer victims — might follow, the API set in motion an ambitious plan to make benzene seem less menacing.

Its members hired a consulting firm, ChemRisk, to try to discredit NIOSH’s Pliofilm study, which had set off such a panic about high leukemia risks among workers.

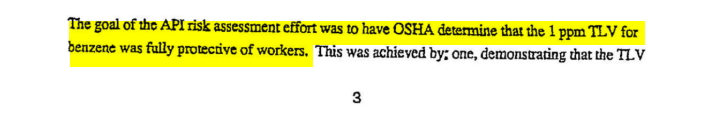

In 1990 ChemRisk president Dennis Paustenbach met with representatives of companies including Chevron, Mobil and ARCO. Minutes from the two-day meeting show he promised to generate a series of papers, to be published in peer-reviewed scientific journals, which would convince OSHA that its 1-ppm exposure limit was “fully protective of workers.”

The first paper, published in 1992, did just that. It concluded that the Pliofilm cancer victims had been exposed to levels of benzene in the 1940s and ’50s that modern-day workers would never see. NIOSH hadn’t accounted for that, the paper’s authors claimed, so the agency had overstated the risk.

A year later a second paper found that chronic exposure to relatively high concentrations of benzene did, in fact, increase the risk of acute myeloid leukemia, or AML. But it played down the idea that the chemical caused other leukemias. This fed into the industry narrative that benzene caused only one type of leukemia, and only after heavy exposures that were no longer seen in the workplace.

Such publications may not sway regulators but are useful in the defense of lawsuits, Michaels, the former OSHA chief, wrote in his 2008 book “Doubt Is Their Product.”

“A jury might be impressed by a one-hundred-page ‘peer-reviewed’ article that claims all of the government science must be wrong, must be ‘junk science,’” he wrote, “whereas the industry’s own ‘sound science’ proves that benzene did not cause this individual’s leukemia.”

Because of this sleight of hand, some would-be benzene plaintiffs with the “wrong” kinds of cancer might be dissuaded from bringing cases. Those who do could face years-long court battles and low-ball settlement offers.

Paustenbach, who now runs a Wyoming-based consulting firm, Paustenbach & Associates, did not respond to requests for comment.

In 1997, the API funded research to dispute the findings of a long-term worker study in China, in which the U.S. National Cancer Institute participated. The study found that benzene could trigger “a spectrum of hematologic neoplasms [cancers] and related disorders in humans,” including non-Hodgkin lymphoma, at exposure levels below 10 ppm.

What was the industry afraid of?

Michaels explained in “Doubt Is Their Product.”

“Should the toxic effects of low-level benzene exposure reported by the original China study become widely accepted by regulators, calls would soon follow for the reformulation of gasoline, for control of emissions from refineries and marketing facilities, and for the clean-up of contamination,” he wrote. “A nightmare for the industry. And then there’s litigation.”

In 2014, the Center for Public Integrity reported that industry documents suggested the oil and chemical industries to that point had spent at least $36 million to challenge the China study.

Andrew DuPont, a Philadelphia lawyer who represents plaintiffs in benzene-exposure lawsuits, said defendants tend to acknowledge that the chemical can cause aplastic anemia, AML and myelodysplastic syndromes — a group of cancers that can lead to AML. Focusing on these conditions can help limit companies’ liability in cases involving non-Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, acute lymphocytic leukemia and myelofibrosis, a blood cancer that causes the accumulation of scar tissue in bone marrow, DuPont said.

“What you have is an industry that knows it’s going to lose profitability if the true extent of benzene’s health hazards is recognized,” he said. “It would cost them a lot of money to take benzene out of gasoline and other products.”

The API’s press office did not respond to requests for comment from Public Health Watch. On its website, the institute acknowledges only that benzene “causes blood disorders [leukemia] in workers exposed to high concentrations.”

One of DuPont’s clients, James Aiello, sued United States Steel and four other defendants in 2016 after developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Aiello told Public Health Watch he was an electrician at a U.S. Steel mill in Pittsburgh from 1964 to 1980 and regularly washed grease off his tools and hands with benzene and Liquid Wrench, a benzene-containing solvent. “We were never told about benzene,” he said. “That was all hushed.”

Aiello, 80, underwent four years of chemotherapy and has been in remission since 2019, when his lawsuit was settled for an undisclosed amount.

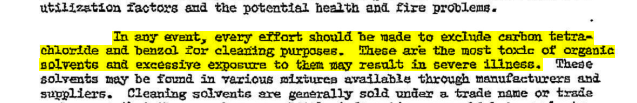

The defendants admitted no culpability. But a 1953 memo, written by U.S. Steel’s Medical Division and obtained by lawyer DuPont, suggests the corporation knew of benzene’s toxicity long before Aiello got sick.

“[E]very effort should be made to exclude carbon tetrachloride and benzol [benzene] for cleaning purposes,” the memo says. “These are the most toxic of organic solvents, and excessive exposure to them may result in severe illness.” Still, DuPont said, U.S. Steel sold benzene-containing waste from coke ovens to the maker of Liquid Wrench from 1960 to 1978. A spokeswoman for U.S. Steel declined to comment.

Bryan Morin cleaned benzene-laced sludge, or “bottoms,” from crude-oil and gasoline storage tanks in Louisiana in the early 1980s. He worked as a contractor at refineries owned by Shell and Chevron, developed multiple myeloma and sued the companies in 2011.

“I would encounter sludge that was at least 2 feet high and inhale strong fumes from the tank bottoms on a daily basis,” Morin said in an affidavit. “I was never warned by anyone from the refineries that benzene could cause cancer, including multiple myeloma and other blood disorders.” He died, at age 47, in 2012.

Eric Williams, the lawyer who represented Morin, settled his lawsuit for an undisclosed sum. He said the refineries “knew the levels of benzene in storage tanks were horrific, yet they chose to let workers go in and clean them without the proper protective gear.”

Shell and Chevron did not respond to requests for comment.

Soaring Demand, Sobering Science

Benzene isn’t going anywhere. In 2022, more than 60 million metric tons of the chemical — 132 billion pounds — were produced worldwide, according to the business-intelligence firm Statista, with a market value of $94 billion. The firm forecasts that global benzene production will reach 76 million metric tons by 2030.

The science, meanwhile, keeps getting more ominous.

In 2017, epidemiologist Infante reported a “significant association” between childhood leukemia and residential proximity to gasoline stations. Two other researchers redid their own meta-analysis of the potential link and found “new evidence for associations of childhood leukemia with both residential proximity to gasoline stations and exposure to benzene.”

In 2021, a comprehensive review and analysis of all human studies that examined the possible relationship between benzene exposure and non-Hodgkin lymphoma confirmed that the two were connected.

A 2022 update of the National Cancer Institute’s original China study found a “clear association” between low-level benzene exposures and benzene poisoning, which “has been linked to a strongly increased development of lymphohematopoietic malignancies” — cancers that include lymphomas and leukemias.

An influential advisory group, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists, now recommends that the eight-hour workplace exposure limit for benzene be set at 0.02 ppm — 50 times stricter than what’s permissible in the United States today. The European Chemicals Agency recommends an occupational benzene limit of 0.05 ppm, 20 times stricter than what OSHA allows.

But OSHA seems unlikely to act.

“OSHA has no plans to update the benzene standard at this time but will continue to monitor scientific developments regarding the health effects of benzene and determine what the Agency can do to best protect employees,” a spokeswoman said in a written statement to Public Health Watch.

She said the agency’s 1987 limit of 1 ppm was considered “the lowest feasible level for industry” at the time and was expected to “reduce the excess risk of leukemia deaths by 90 percent.” She acknowledged, however, that “many authoritative bodies require or recommend occupational exposure limits that are lower” than the OSHA number. The agency lists some of these alternative limits on its website.

Meanwhile, scientists are increasingly worried about benzene exposure beyond the workplace — especially in communities where people’s homes are uncomfortably close to polluting industries.

According to the EPA’s Toxics Release Inventory, more than 8.8 million pounds of the chemical were discharged into the air in the United States in 2022.

Because the federal government hasn’t set an ambient federal standard for benzene — as it has for, say, sulfur dioxide, a respiratory irritant — states are largely left to decide how much of the chemical the public can tolerate. Texas is at one end of the spectrum. It says people can be exposed to as much as 180 ppb in an hour without experiencing serious health effects. California is at the other end of the spectrum, with a safety guideline of 8 ppb — 22 times stricter.

The EPA has taken targeted actions against benzene over the years.

In 1989, it established national emission standards for hazardous air pollutants, including benzene, from stationary sources that use certain processes, such as chrome-plating operations and copper smelters. An agency spokeswoman said the rule “sets an upper limit of acceptable risk at about a 1-in-10,000 … lifetime cancer risk for the most exposed person.” Violators of the standards face civil or criminal penalties.

Because most benzene in the environment comes from cars and trucks, the EPA issued a rule in 2007 requiring oil refiners to gradually reduce the amount of benzene in gasoline, from about 1% by volume to 0.62%. As a result, the agency spokeswoman said, “benzene levels have decreased significantly over time.”

In 2015, the EPA required refineries to monitor benzene emissions at their fence lines and take other protective measures. The API complained about the regulation, saying it would impose “enormous costs while offering dubious environmental benefit.” But the rule remains in effect. According to the EPA, benzene concentrations at refinery fence lines have fallen by an average of 30%.

Now, under the Biden administration, the EPA is going after chemical-manufacturing plants that release benzene and other hazardous air pollutants. Under the agency’s proposal, about 200 of these facilities would have to improve the efficiency of their flares and do more to stop leaks. Plants that use, emit, produce or store any of six air toxics — benzene, vinyl chloride, 1,3-butadiene, ethylene dichloride, chloroprene and ethylene oxide — would have to monitor for the chemicals at their fence lines.

Borrowing a page from the API, the chemical industry’s main trade group predicts doom if the rule takes effect next spring, as expected. In a comment submitted to the EPA, the American Chemistry Council warned that supply chains could be disrupted and many facilities forced offline, “all without a meaningful benefit for public health or the environment.”

Moms Clean Air Force, an advocacy group with 1.5 million members, is unsympathetic to such arguments, noting in its official comment, “The companies covered by these newly proposed rules release extraordinary amounts of carcinogens and other hazardous chemicals into the air. They have done so for generations, with cruel disregard for the devastating impacts on communities around their facilities. And people have paid with their health.”

Jana Cholakovska contributed to this story.