Scientists are increasingly alarmed by the airborne particles routinely released by power plants, petrochemical companies, motor vehicles, concrete plants and other sources. Their concerns are so serious that the Biden administration is wielding a rarely used authority to tighten regulations for these microscopic particles, which hundreds of scientific articles have linked to heart disease, breast and lung cancer, Alzheimer’s and other grave health problems.

A Public Health Watch analysis conducted by two researchers shows that Texans need the extra protection.

Their analysis estimates that 8,405 Texans died in 2016 from exposure to particulate matter, known as PM2.5 because the particles are 2.5 microns in width or smaller. That’s about 30 times smaller than a human hair.

The analysis also linked particulate pollution to an estimated 24,575 new Alzheimer’s cases, 7,823 new asthma cases and 2,209 strokes in Texas. It used 2016 NASA satellite data (the most recent available) that measured the concentration of PM2.5 in the air across the state, as well as state and national health databases.

The analysis was done by data researcher Luke Bryan and Dr. Philip Landrigan, an epidemiologist at Boston College known globally for his work on air pollution. A similar study they did in Massachusetts was published last year in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Environmental Health. Bryan and Landrigan used the same methodology in the work they did for Public Health Watch.

They estimated that Harris County, which includes Houston and thousands of oil refineries and petrochemical facilities, had the most deaths in 2016 from particle pollution: 1,372, or 31 people per 100,000. It also had the census tracts with the highest concentrations of PM2.5.

Dallas County had an estimated 674 deaths, or 27 per 100,000. Bexar County, which includes San Antonio, had 572 deaths, or 30 per 100,000.

The Deadly Toll of Fine-Particle Pollution

View an interactive map that shows how fine-particle pollution impacts the health of communities across Texas.

The annual death rate in Texas has likely risen since the NASA data was collected because the petrochemical industry — a major source of particulate matter — has grown dramatically since 2016.

Eight petrochemical plants have been built in Texas in the past seven years and 30 have expanded, according to Oil and Gas Watch, an arm of the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project that tracks the oil, gas and petrochemical industries. If those companies produce as much particulate matter as their state-issued permits allow, they would release almost 1,300 tons of PM2.5 each year. That’s more than a third of the PM2.5 produced by all of Harris County’s major industries — combined — in 2021.

“It would stand to reason those new factories are worsening the air pollution,” Landrigan said. “But we won’t know for sure until we get the next [data] update.”

How they did it: To estimate deaths and health conditions attributable to fine-particle pollution in Texas, researchers Luke Bryan and Dr. Philip Landrigan plugged demographic and air-pollution data into a formula commonly used in epidemiological studies. The formula measures the strength of relationships between concentrations of fine particles — known as PM2.5 — and specific health effects, using data from previous studies that tracked air pollution and disease rates over many years. To estimate the number of deaths and illnesses linked to PM2.5 in Texas, the researchers then ran the calculations through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s BENMAP software, which is used to predict the health impacts and economic value of changes in air quality.

Smaller and deadlier

The smallest particles, which are 1 micron or less in width, are of special concern to scientists, said George Thurston, a New York University public health professor who has studied particulate pollution for more than 30 years. Most of them are produced by industrial facilities or by combustion from car and truck exhaust, gas stoves and other sources.

These tiny particles can pierce the lungs, enter the bloodstream and settle in organs, Thurston said. They can also ferry toxic chemicals used or produced in industrial facilities into the circulatory system, a region of the body these chemicals normally couldn’t penetrate.

Thurston’s most recent research, published in July in the journal Environmental Research: Health, shows that particulate matter is even more toxic than scientists previously assumed.

“It’s right up there with things like diabetes and smoking,” he said. “It’s been estimated that outdoor air pollution from particulate matter causes about 100,000 deaths per year in the United States. So it’s a very important and problematic pollution exposure that we’re getting.”

No level of exposure is without risk, according to the World Health Organization. It recommends an annual average of 5 micrograms per cubic meter of air (μg/m3) for PM2.5.

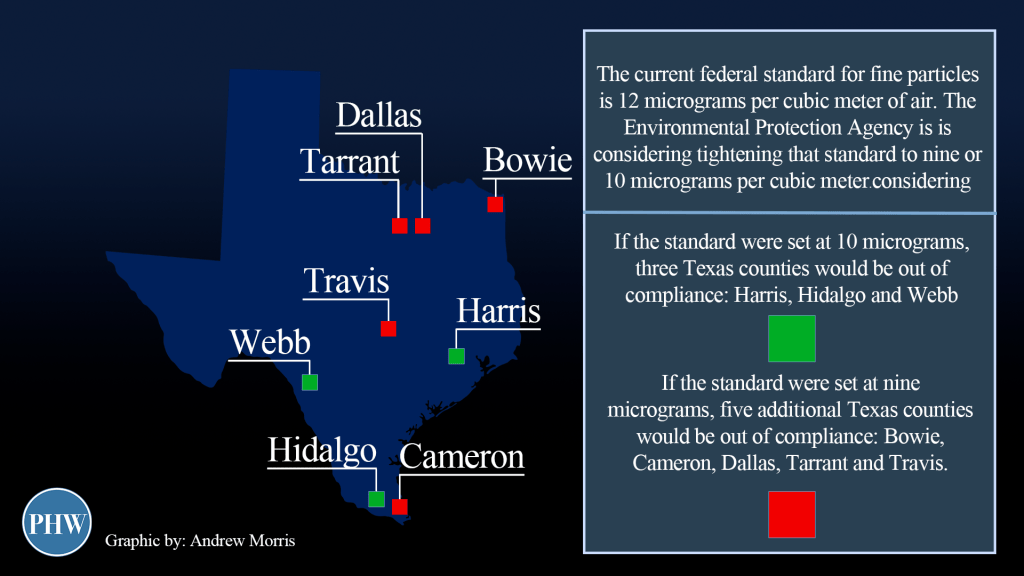

The current U.S. standard is more than double that — 12 μg/m3 — even though the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has tightened the rule several times over the years. The Trump administration ended that trend in 2020 when it declined — against the recommendation of EPA scientists — to tighten it again.

Normally, the standard wouldn’t be revisited until 2025. But the new and alarming research prompted the Biden administration to act sooner. The limit it is considering — between 9 and 10 μg/m3 — is expected to be finalized by the end of the year.

Industry groups and their supporters are digging in to fight the change.

Nineteen state attorneys general, including Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, signed a letter in April accusing the EPA of exceeding its authority. Paxton argued in a news release that tightening the standard would “crush economic development in different parts of the United States.”

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, or TCEQ, the state agency charged with protecting public health, filed a public comment with the EPA saying the rule lacks scientific backing.

A national coalition of 20 industry groups submitted a 200-page comment saying the EPA hasn’t justified the need to review the standard early and hasn’t estimated its “full costs and economic impacts.” They said complying with the rule could cost their companies between $1 billion and $9.2 billion to install pollution control equipment.

Clean-air advocates, health organizations and many scientists say the proposed standard is too lenient and won’t do enough to protect the public from a pollutant whose dire health impacts are increasingly clear. They want it to be 8 μg/m3 or even lower.

“There’s a lot of science that’s undeniable, let’s put it that way,” Thurston said.

Fine particles linked to growing list of health effects

Microscopic, airborne particles can pierce the lungs and travel through the bloodstream to attack organs. As more research emerges on the harm they inflict, the Biden administration is looking to tighten regulations on these particles, which cause an estimated 100,000 deaths in the U.S. each year. Click on a health effect to see supporting research.

The EPA’s own analysis validates that concern. The agency estimates that tightening the level to 9 μg/m3 would save 4,200 adult lives every year. Ratcheting it down to 8 μg/m3 would save 9,200 lives — more than double that.

Thurston said the EPA could solve a big part of the particulate problem by creating a new standard for the tiniest particles — those that are 1 micron or less in width. That would effectively separate particles from oil refineries, power plants and petrochemical facilities from the larger particles from natural sources, like soil and sand, which are currently included in PM2.5 readings.

“So we focus in on the sources that are most important, and we’d be able to actually do something about it,” Thurston said.

Nikolaos Zirogiannis, an environmental economist at Indiana University, warns that particulate pollution threatens even those who don’t live directly next to an industrial source.

“The closer you are to an emissions source, the more affected you are by it,” Zirogiannis said. “But you are getting the impacts of those emissions even if you live 20 miles away from a [concrete] batch plant, because those PM releases affect air quality within the entire county and sometimes in nearby counties.”

Batch plants are typically small operations that mix sand and gravel with a binding powder to make batches of concrete, releasing particulate matter into the air.

Big offenders

The top four particulate polluters in Texas are coal-fired power plants, followed by an Exxon Mobil oil refinery in Baytown, outside Houston, according to the TCEQ’s emissions inventory . While coal-fired power plants are gradually closing and oil refining is expected to stagnate or slow, the petrochemical industry is expanding, primarily because of increased demand for plastics.

Like all major industries, petrochemical companies can legally release specified amounts of particulate matter during regular operations. But because Texas’ environmental regulations are notoriously weak, companies rarely face serious penalties if they exceed those amounts.

A recent Public Health Watch and Texas Tribune investigation found that the TCEQ and the EPA knew for almost two decades of numerous leaks at a 265-acre chemical storage facility in Harris County but did little to address them.

In 2019, tanks at an Intercontinental Terminals Company facility erupted in flames, releasing high levels of the carcinogen benzene and launching a black cloud of fine particles. The cloud was so large that the National Weather Service and the Interagency Modeling and Atmospheric Assessment Center, a federal team that models chemical releases from major fires, tracked it for five days and estimated its particulate matter every six hours. Local officials used their models to monitor the fire’s health hazards and make public health decisions.

Four days after the fire started, Mary Ann Contreras, an assistant funeral home director in the city of Pasadena, watched the cloud blot the sky above a funeral she was working 5 miles away. When she returned to her car 45 minutes later, her windshield was covered with black particles.

By this time Contreras said her head was hurting, and she was gasping for air. At one point, she stopped her car and vomited on the side of the road.

Contreras drove to the emergency room where, she said, a doctor told her “high exposure to chemicals” caused her symptoms.

“I was scared to go to sleep that night,” said Contreras, who is among more than 300 people who filed lawsuits against ITC after the accident. “I was like, ‘Am I going to wake up?’”

Less than nine months after the fire, the TCEQ gave ITC a new chemical permit that allows it to operate until 2029.

Thurston, the NYU professor, said that proving that pollution from a specific plant caused a specific person’s illness is almost impossible. But in his recent paper, he was able to show how pollution from a single plant can affect the health of a nearby community.

He and lead researcher Wuyue Yu studied what happened in Pittsburgh neighborhoods after a nearby coal-processing plant closed in 2016. They found that particulate readings around the plant fell by 20% — from a three-year average that exceeded the federal standard to a level that was far below. Even more striking was the 66% drop in arsenic embedded in the particles. Arsenic inhalation has been linked to lung cancer and a rare form of liver cancer.

In the weeks immediately after the plant shut down, emergency room visits for heart problems declined 42%. And there were, on average, 33 fewer hospitalizations for heart disease per year in the three years after the plant closed compared with the final three years it was operating. Preliminary data shows similar improvement for respiratory problems.

“This is a good example, I think, to actually give evidence that … targeting their emissions did benefit the health of the local people,” said Yu, a PhD candidate at NYU’s medical center.

The batch plant exclusion

Batch plants routinely release fine particles into the air. But in Texas they are considered minor sources of pollution so they aren’t required to report their emissions.

Texas has 534 batch plants, the most in the country, according to the 2017 U.S. Economic Census. Clouds of dust routinely drift off the plants’ machinery and the trucks that haul rocks and sand to and from their worksites.

Deirdre Diamond became acquainted with batch plants in 2020 after she and her husband moved their family to Gunter, Texas. Diamond, a respiratory therapist, was looking for open spaces and cleaner air for their six children. The middle-class town about an hour outside Dallas seemed just right. With 2,500 residents, it’s surrounded by thousands of acres of mostly undeveloped land populated by grazing Texas Longhorns.

But Diamond’s days were soon consumed by her fight against the industries encroaching on her town. A company that makes concrete pipelines was built 5 miles from her house. Five batch plants were built across from the pipeline company, and a sixth is on the way.

Fine particles from the industrialized block whip into the air. Hundreds of trucks traveling to and from the plants barrel past the town’s schools each day. Diamond’s previously healthy children started getting sick, usually on days when the pollution was worse.

Last December, Diamond began homeschooling them.

“We all moved out for country life — but not for pollution,” she said. “Our children are our greatest investment. … If we can’t protect them at school, then what are we doing?”

Diamond has submitted dozens of complaints to the TCEQ. She even paid for independent air modeling of the batch plants’ pollution. It found that their combined emissions exceed the federal standard for both PM2.5 and PM10, a larger category of particles with widths of 10 microns or less. She submitted the findings to the TCEQ but was told the agency only regulates emissions from individual plants, not collective emissions from groups of plants.

New research from Zirogiannis, the Indiana University professor, shows that, collectively, batch plants are a major source of particulate pollution in Harris County, where one-fourth of the state’s batch plants operate. He reached that conclusion by using information from Chicago, which also has a high concentration of batch plants. Illinois state law requires batch plants to report emissions, and Zirogiannis found that Chicago’s batch plants emit only about 30% of the particulate matter the state allows them to release.

Using that calculation in Texas, Zirogiannis estimates that, collectively, Harris County’s 131 batch plants emit at least 38 tons of PM2.5 each year. That’s more than a quarter of the 146 tons emitted by the median Texas oil refinery.

If those 131 plants emitted all they are allowed to under their TCEQ permits, they would release 111 tons of PM2.5 annually. That’s about three-quarters of what the median refinery emits.

EPA weighs in

Texas’ particulate problems have drawn the attention of the EPA.

Last year, the agency announced it was investigating the TCEQ for a potential civil rights violation based in part on complaints that it had failed to protect communities of color from batch-plant pollution.

Batch plants, like other industrial facilities, are disproportionately located in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color. These neighborhoods also face disproportionate pollution from motor vehicles, which contribute heavily to ozone — the main ingredient in smog — and particle pollution. Black Americans are more than three times as likely to die from cardiovascular disease caused by fine particles than white Americans, according to a paper published in August by Yale researchers. Latinos have a slightly higher risk than white Americans.

The EPA also denied the TCEQ’s request for a one-year extension to comply with the federal ozone standard. Again, the agency cited the disproportionate effect of particle pollution on communities of color.

Earlier this year the TCEQ announced it will tighten its permitting requirements for batch plants. They’ll be given a yearly production limit and be required to reduce airborne dust.

A handful of counties — including Harris and seven bordering counties — will also be required to place more distance between batch plants and neighboring properties.

But Texas still won’t require batch plants to monitor or report their emissions.

Josh Leftwich, president of the Texas Aggregates and Concrete Association, or TACA, said that many of the new regulations are already “standard best practices,” including dust suppression and emission controls. “TACA works very closely with TCEQ and all regulating agencies to ensure safe and efficient operations,” Leftwich said.

Potential legal challenges

Even the most lenient standard being considered by the Biden administration would force Texas to strengthen its permitting requirements for industrial polluters.

If the particulate standard is set at 10 μg/m3, three Texas counties — Harris, Hidalgo and Webb — will likely be out of compliance, according to EPA data.

If it’s set at 9 μg/m3, five more counties likely won’t comply: Bowie, Cameron, Dallas, Tarrant and Travis.

Industry groups have challenged previous changes to the particulate standard, but those efforts failed. The 1997 standard was delayed, but the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the EPA’s favor in 2001.

Public Health Watch reached out to two trade groups — the Texas Chemical Council and the Texas Oil and Gas Association — to ask if they will sue to try to block the latest change, but neither responded. A lawyer for the industry coalition that filed the 200-page comment opposing a stricter PM2.5 limit also didn’t respond.

Ilan Levin, associate director of the Environmental Integrity Project, expects industry and states like Texas to sue when the standard is finalized. But he doesn’t think their arguments will stand — even before the conservative-leaning Supreme Court.

The EPA is “going to rely very heavily on the medical data and the science,” Levin said. And science clearly “shows that people are being harmed by fine particle pollution at levels that are lower than what the current standards allow.”

The Fund for Investigative Journalism supported this project.