Let’s establish some baselines.

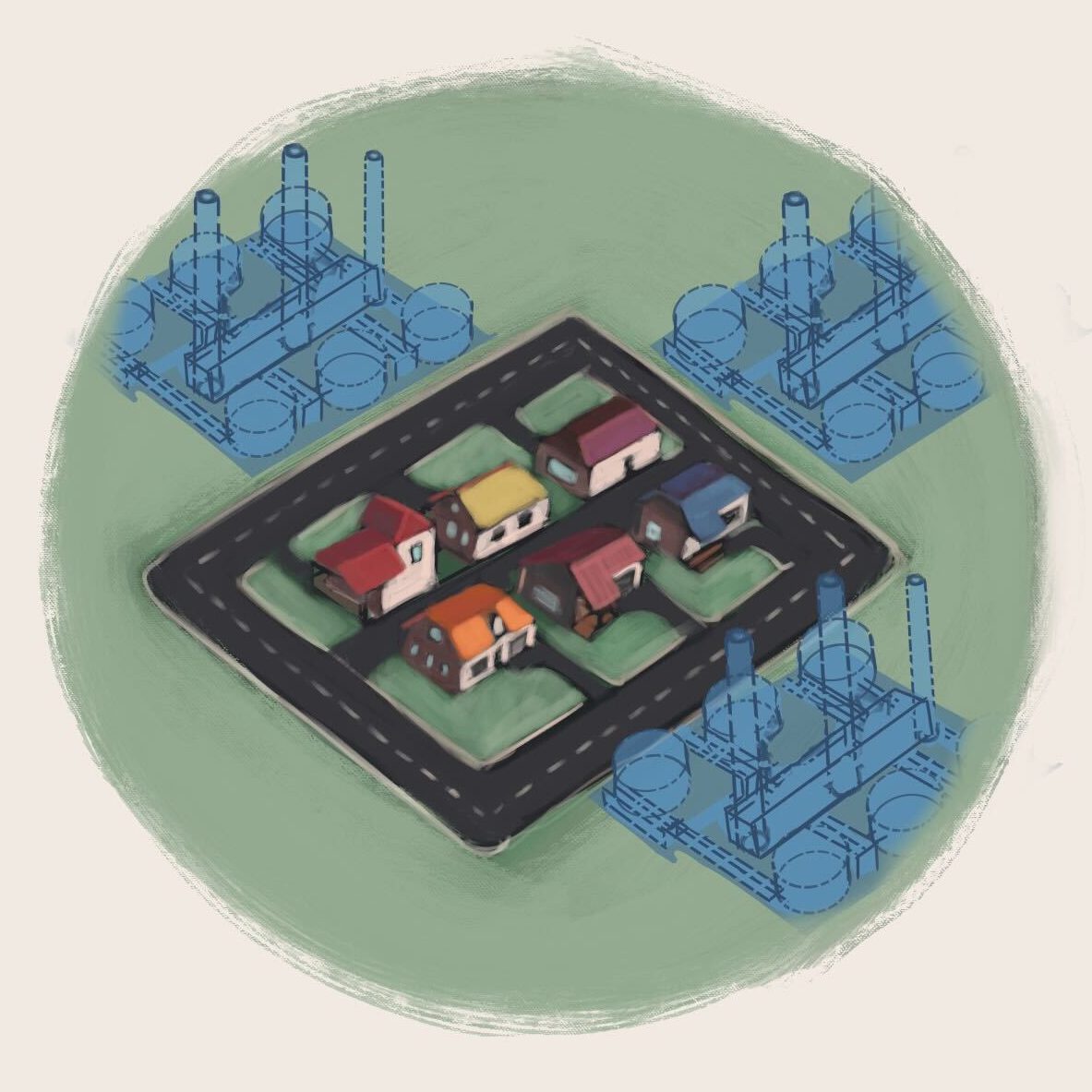

Texas is responsible for more greenhouse-gas emissions than Saudi Arabia or the global maritime industry. Its oil, gas and petrochemical operations discharge tens of millions of pounds of toxic pollutants into the air each year, comprising almost one-fifth of such releases in the United States. It is the nation’s top emitter of the carcinogens benzene, ethylene oxide and 1,3-butadiene.

It accounts for 75% of the petrochemicals made in the U.S. It is an engine of the world’s plastics industry, whose products clog oceans and landfills and, upon breaking down, infuse human bodies with potentially dangerous microplastics.

Despite all of this, the state’s commitment to fossil-fuel infrastructure is unwavering, driven by economics. Oil and gas extraction, transportation and processing contributed $249 billion to the state’s gross domestic product and supported 661,000 jobs in 2021, according to the most recent reports from the Texas Economic Development & Tourism Office. An industrial construction spurt is well into its second decade, with little sign of slowing.

Since 2013, 57 petrochemical facilities have been built or expanded in the state, according to the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project’s Oil & Gas Watch, which tracks these activities. Over half are in majority-minority neighborhoods, the group’s data show.

The odds are in their favor: In the past quarter-century, the TCEQ has denied less than 0.5% of new air permits and amendments, often required for plant expansions.

For six months, Public Health Watch has been reviewing TCEQ permits, analyzing air-quality and census data and talking to scientific experts, advocates, elected officials, industry representatives and residents of Harris and Jefferson counties to try to capture the scope and potential health consequences of the petrochemical buildout.

Here are 13 scenes from that buildout.

Hover over an image to read a synopsis and click to scroll to the story. Then use the navigation bar on the side of the page to click between scenes.

Illustrations by Andy Morris-Ruiz. Visualizations by Shelby Jouppi.

Home of Spindletop booms again

Jefferson County

Jefferson County has a quarter-million residents and stretches from Beaumont in the northeast to McFaddin National Wildlife Refuge on the Gulf of Mexico. Its Spindletop field birthed Texas’s first full-scale oil boom in 1901; today it is once again an axis of industry zeal.

Just off Twin City Highway, where Nederland meets Beaumont, cranes are assembling a plant that will produce anhydrous ammonia and other chemicals used to make fertilizer and alternative fuels. According to state permits issued to owner Woodside Energy, the facility is authorized to annually add almost 80,000 pounds of nitrogen oxides, which can cause acute and chronic respiratory distress, to Nederland’s air. Nitrogen oxides also contribute to ground-level ozone pollution, the primary component in smog. Uncontained, ammonia can sear the lungs and kill in sufficient concentrations.

Four people formally objected to the facility’s expansion last summer but were unable to stop it. Officials in Jefferson County embraced the plant, granting Woodside a 10-year property-tax exemption, and a $209 million tax abatement from the Beaumont Independent School District.

About two miles to the southeast of Woodside, Energy Transfer wants to erect a large ethane cracker on the Neches River. The hulking plant will heat ethane, a component of natural gas, to extremely high temperatures, “cracking” the molecules to make ethylene, a building block for plastics. According to Energy Transfer’s permit application, the cracker would be allowed to release nearly 10 million of pounds of volatile organic compounds, or VOCs, which contribute to ozone and can cause effects ranging from throat and eye irritation to cancer, along with nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide, another smog-forming chemical that interferes with the body’s oxygen supply.

The TCEQ told Public Health Watch in an email that the project “is protective of human health and the environment and no adverse effects are expected to occur.

There were seven formal objectors to the ethane cracker, among them Reanna Panelo, a lifelong Nederland resident who was 23 when she wrote to the TCEQ two years ago. “It is not fair nor is it morally right to build such a monstrous and horrendous plant designed to kill the surrounding area, residents and environment, for company gain,” wrote Panelo, who said generations of her family had been tormented by cancer. The TCEQ executive director is processing Energy Transfer’s permit application, despite comments submitted in October by the Environmental Integrity Project alleging the project could violate ambient air-quality standards for particulate matter — fine particles that can exacerbate asthma, cause heart disease and contribute to cognitive decline. The Nederland Independent School District authorized a $121 million tax break for Energy Transfer.

Nine miles south of Nederland, in Port Arthur, two ethane crackers are poised for expansion and three new petrochemical facilities are planned, according to Oil & Gas Watch.

“It’s the worst possible situation you can imagine,” said John Beard, a Port Arthur native and founder of Port Arthur Community Action Network, an environmental advocacy group. “You’re living in a toxic atmosphere that with every breath is potentially killing you.”

Air quality in Jefferson County has improved over the years — mostly a product of stricter regulation — but is still far from pristine. The American Lung Association gave the county an “F” for ozone pollution in its 2025 State of the Air Report Card.

A pungent haze occasionally envelops the county, portions of which have some of the highest cancer risks from air toxics in the nation, according to the Environmental Defense Fund’s Petrochemical Air Pollution Map. Indorama Ventures in Port Neches is one of the main drivers of risk — it makes the potent carcinogen ethylene oxide and releases more of the gas into the air than any other facility in the U.S., federal data show. Peter DeCarlo, an atmospheric chemist and a professor at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering, and a team of fellow scientists recently drove an air-monitoring van through neighborhoods bordering Indorama. They measured levels of ethylene oxide “greatly exceeding what is acceptable for long-term exposure,” DeCarlo told Public Health Watch.

The county’s level of particulate matter already exceeds national air-quality standards. Jefferson County spent 18 years in violation of the standard for ground-level ozone, but improved after 2009. Now, the county’s ozone levels are creeping upward again. DeCarlo said that the new sources of pollution slated for the region could push the county over the limit again — subjecting it to tougher oversight — and worsen its fine-particle problem.

In a statement to Public Health Watch, Woodside said its ammonia plant is 97 percent complete and represents “a $2.35 billion investment in American energy, supporting approximately 2,000 construction jobs and hundreds of permanent ongoing jobs . . . Once operational [it] is expected to increase US ammonia production by more than 7%, strengthening domestic agriculture, food production and manufacturing, while potentially doubling US ammonia exports.”

The company said it met with four residents who filed comments with the TCEQ and appreciated “the strong community support for the project.”

Energy Transfer and Indorama Ventures did not respond to requests for comment.

Flaws in Texas air permitting

By its own description, the TCEQ “strives to protect our state’s public health and natural resources consistent with sustainable economic development.” The agency is supposed to carefully scrutinize air permits with an eye toward limiting pollution, and to make sure Texans have a say in the process. A Public Health Watch analysis found, however, that in the past 25 years the TCEQ has not denied a single permit for a new, major source of air pollution, and has turned down only three new construction permits. It has denied only four of almost 13,000 permit amendments, often required for plant expansions, and less than 0.5% percent of permit renewals.

In emails to Public Health Watch, the TCEQ said it denies a permit only if the agency’s staff determines the proposed project “does not meet applicable regulatory requirements.” The agency said it notifies companies if their paperwork is deficient, and applicants “frequently” make the required changes.

But environmental lawyers who practice in Texas say the state’s permitting system seems designed to enable industrial development, not protect the public. Here are five flaws they have identified.

Click below to read details and the TCEQ’s response.

Facilities can have dozens or even hundreds of active permits that are frequently changed, making it difficult for experts, let alone the public, to keep track. Public Health Watch found that, on average, one new permit application, renewal, revision or amendment is filed about every hour. Last year, the state fielded almost 8,000 of these industry requests, according to TCEQ data.

The TCEQ declined to grant Public Health Watch an interview, but did respond by email to the alleged deficiencies in the permitting process. A spokesperson wrote that the agency “ensures all projects are reviewed in accordance with state and federal statutes and regulations,” and has made improvements to public engagement. The spokesperson cited as an example a new map-based search tool that allows people to find air, water and waste permits in specific areas.

Bills that would have required the TCEQ to conduct cumulative-effects reviews in its permitting process have died in committee every legislative session since 2017. The legislation would have forced the agency to assess how emissions from facilities near a proposed project can combine and compound to create more serious health risks.

The TCEQ said it does consider current air quality and emissions from nearby plants when weighing permit applications — but only for individual chemicals, and only if the proposed project could “cause or contribute to an exceedance” of federal standards.

The agency allows an “affected person” to formally challenge a permit through a contested-case hearing, where parties can submit evidence and the company’s experts are cross-examined. But the state has been making arbitrary determinations of who is “affected” said Erin Gaines, an attorney and a clinical professor at the University of Texas School of Law’s Environmental Law Clinic. People who live, work and fish within a few miles of a facility, for example, have been rejected without a clear explanation. A recent Texas appellate court decision, which Gaines is challenging, held that once the TCEQ decides someone is unaffected by a project, that person can’t appeal the permit in court.

The TCEQ declined to comment on the issue.

“The game that polluting industries often try to play in Texas is getting major industrial projects categorized as ‘minor,’ because this often means weaker pollution control requirements,” Gabriel Clark-Leach, a lawyer who has spent the past 15 years litigating petrochemical permits for the Environmental Integrity Project, wrote in an email. ”Some companies will make their potential emissions seem smaller by applying for multiple ‘minor’ permits instead of a major permit, as they should, or by using questionable calculations that may go unchallenged by state regulators.”

The TCEQ told Public Health Watch it has developed a process “to prevent a large construction project from being split into multiple smaller projects,” and has created “a variety of guidance and fact sheet documents to properly classify major or minor projects.”

Chase Porter, a staff attorney with Lone Star Legal Aid in Houston, said the TCEQ doesn’t provide information about the health risks of new sources of air pollution in ways most people would understand. The reason, he thinks, is that the agency genuinely believes compliance with the Clean Air Act eliminates any such risks.

“I don’t think it’s really scientifically debatable that you can still have health consequences without violating the [act],” Porter said.

Asked if it subscribed to this logic, the TCEQ said it “issues permits that are protective of public health consistent with all applicable state and federal rules and laws, including those promulgated to implement the Clean Air Act.”

Historic Black neighborhood threatened with extinction

Beaumont, Jefferson County

The Charlton-Pollard neighborhood, on Beaumont’s south side, was established in 1869 by freed slave and school founder Charles Pole Charlton. In the mid-20th century it was a cultural hub — home to Beaumont’s “Black Main Street” and some of the oldest Black churches and schools in the city. It was part of the Chitlin’ Circuit, a group of performance venues during the Jim Crow era, which hosted James Brown, Ray Charles and other luminaries.

Segregation, disinvestment and expanding industrial operations — railways, an international seaport and a petrochemical complex — gradually eroded Charlton-Pollard’s rich culture and institutions. Stores, schools and a hospital have closed, and now the buffer between the north end of the neighborhood and advancing industrial development is thinning.

The Port of Beaumont has acquired 78 parcels in Charlton-Pollard’s sparsely populated northeastern corner since 2016, property records show. This year it paved a lot the size of 18 football fields in their place, where it plans to store cargo, including building materials for new and expanding petrochemical plants. The lot lies across the street from the 97-year-old Starlight Missionary Baptist Church and two blocks from Charlton-Pollard Elementary School.

“The port recognizes the deep history of Charlton-Pollard and remains committed to operating responsibly and respectfully within that framework,” said Chris Fisher, the port’s director and CEO. He said he and his team have been transparent with the Charlton-Pollard Neighborhood Association, only developing in a specially zoned “transitional area” in the northeastern corner. In the 1990s and early 2000s, some residents asked the port to buy their properties, Fisher said. Later, after plans for the paved lot were solidified, the port began offering property owners 50% to 100% above appraised value and, in some cases, $15,000 relocation allowances, he said.

“We kind of made sure that everybody that we dealt with was better off than before we did anything,” Fisher said. The port condemned properties when owners couldn’t be located or had unpaid taxes, he said.

The neighborhood association’s president, Chris Jones, a 45-year-old former Beaumont mayoral candidate, said the port’s acquisitions are “the continuation of a long pattern. One where Black neighborhoods were first under-documented, then under-invested, and ultimately treated as expendable in the path of industry.”

When residents sold their properties, they “were navigating declining property values, loss of services, and the clear signal that the area was being prioritized for industrial use,” Jones said. “In that context, selling is often less about choice and more about survival.”

He worries that the removal of trees and the addition of pavement will intensify heat and worsen noise pollution for those left in the neighborhood. Rail traffic supporting local industry has already increased, he said, and his status as an Army veteran makes him “vexed at the sound of a horn.” Jones and some allies hope to win historical designations for several churches in Charlton-Pollard to stave off further industrial encroachment.

Environmental hazards are not new to Charlton-Pollard. A refinery now owned by Exxon Mobil was built less than a mile away in 1903. Almost a century later, residents filed a complaint with the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights, accusing the TCEQ of allowing the company to pollute above safe levels, increase emissions without public input and exceed permitted limits without penalty. The case was settled in 2017 after the TCEQ agreed to install an air monitor near the site and hold two public meetings. Charlton-Pollard still lies within the 99th percentile nationwide for cancer risk from air pollution, according to the Environmental Defense Fund.

[Residents] were navigating declining property values, loss of services, and the clear signal that the area was being prioritized for industrial use. In that context, selling is often less about choice and more about survival.

chris jones, president of the charlton-pollard historical neighborhood association

In addition to the refinery, Exxon Mobil now operates a chemical plant, a polyethylene plant and a lubricant plant within the complex; last year the company said it plans to build a chemical-recycling facility there as well. Six more petrochemical projects are planned by other companies within five miles of Charlton-Pollard.

In short, anyone who hasn’t been bought out by the port may breathe increasingly dirty air. Jefferson County is already violating the EPA’s standard for particulate matter, and diesel-burning trains and maritime vessels accommodating the industry expansion are large emitters of fine particles, as well as smog-forming nitrogen oxides.

Most infuriating, Jones said, is the idea that industrial development in Jefferson County is being underwritten in part by tax breaks even as Beaumont’s basic infrastructure — roads, sewage treatment — crumbles. Not long ago, he said, he saw “fecal waste” collecting in the Irving Avenue underpass. “The shit just rolled onto the street.” (Voters approved a $264 million bond package in November to improve streets and drainage)

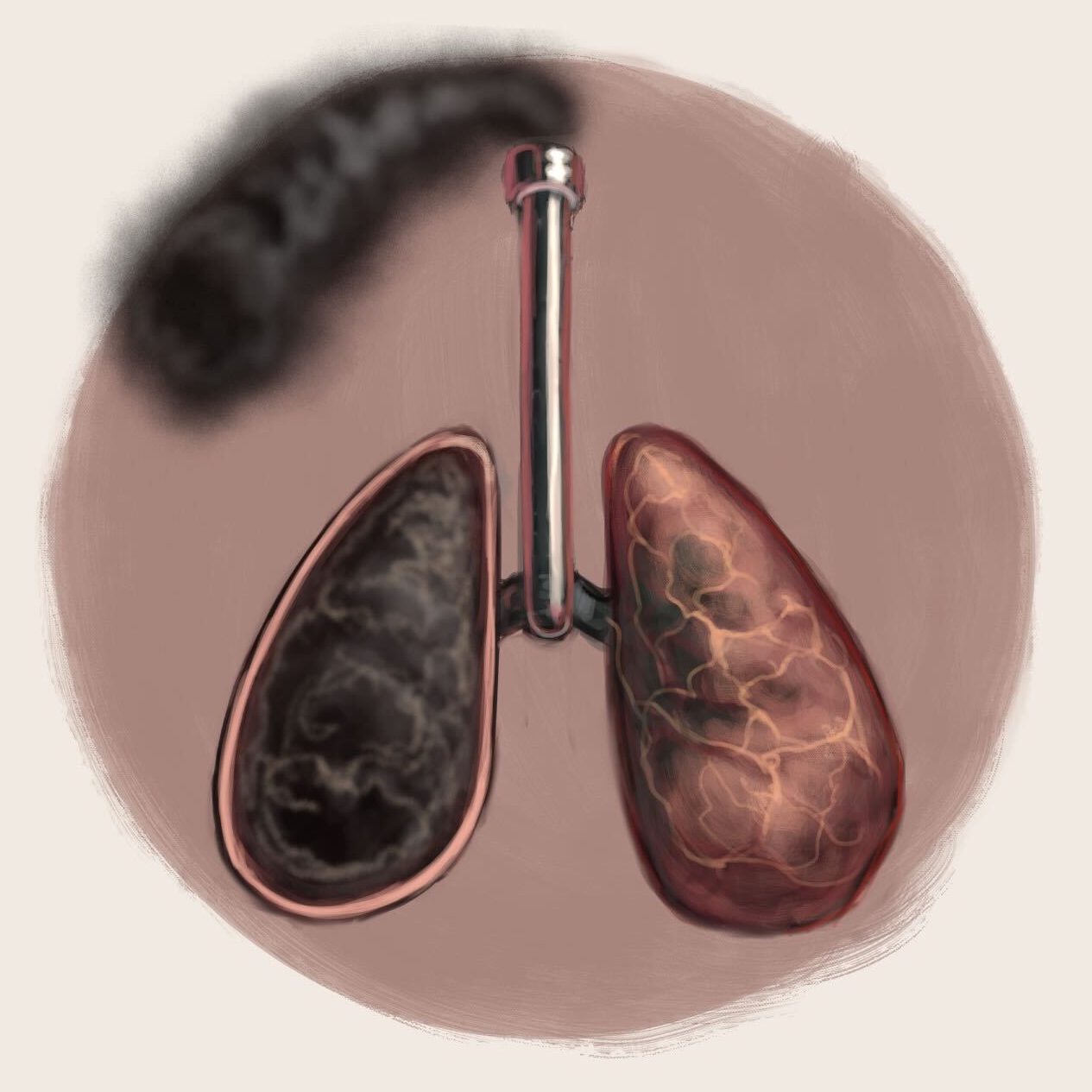

Fine particles, ozone and the body

In addition to spewing carcinogens like benzene and 1,3-butadiene, petrochemical plants release large amounts of “criteria pollutants” — the six common airborne substances the EPA regulates most closely. Regions across the country struggle to meet federal air-quality standards for two of these in particular: ground-level ozone and particulate matter.

Dr. John Balmes, a professor emeritus at the University of California Berkeley School of Public Health, is a physician advisor to both the EPA and the California Air Resources Board, which regulates air quality in a state that’s had serious ozone and particulate-matter problems for years. He’s researched the effects of both pollutants on the body and helped craft EPA standards for them. Balmes said plant emissions will represent only a portion of particulate and ozone pollution from the petrochemical expansion in Texas. Transportation — diesel trucks, trains and ships — will add to the burden, he said. (Railyards and ports are often located in low-income and minority neighborhoods, like Charlton-Pollard.)

Particulate matter and ozone can wreak havoc on the body, Balmes said.

Fine particles, known as PM2.5, are about 20 times smaller than a human hair. When they’re inhaled, they don’t break down, and the body’s immune cells remain in a heightened state of response. Their ability to fight off infection is weakened.

Fine particles often make their way into the bloodstream and trigger cardiovascular problems, such as heart attacks and congestive heart failure. They can also accumulate in the brain, contributing to cognitive decline and strokes.

A 2023 analysis conducted for Public Health Watch by two researchers estimated that 8,405 Texans died from fine-particle pollution in 2016. Exposure to the particles also led to thousands of new cases of Alzheimer’s, asthma and strokes, the researchers found.

Last year, an EPA advisory board, on which Balmes served, recommended tightening the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM2.5. The EPA said the new standard would prevent 4,500 premature deaths and yield $46 billion in net health benefits over more than a decade. According to federal data, 16 Texas counties, including Jefferson, violate the new standard, which the Trump administration has vowed to abandon.

Adding 35 petrochemical plants to a region that is already in serious ozone [violation] is the wrong way to go in terms of public health.

dr. john balmes, physician advisor to the epa and california air resources board

Environmental groups and regulators have been fighting ozone pollution for more than 70 years.

Ozone gas is formed when two pollutants — VOCs and nitrogen oxides — are released from stacks and tailpipes and react in the presence of sunlight. When ozone enters the body, it chemically burns the respiratory system, leading to inflammation. It’s so caustic that it can break down synthetic rubber. Acute exposure can worsen asthma; chronic, high-level exposure can cause permanent lung damage.

The eight-county Houston-Galveston-Brazoria area, with roughly 7.2 million people, has been under continual threat from ozone for two decades. It spent over half of that time classified as being in “serious” or “severe” violation of the EPA’s eight-hour standards. Still, 35 petrochemical projects in the region have been announced or permitted by the TCEQ.

“Adding 35 petrochemical plants to a region that is already in serious ozone [violation] is the wrong way to go in terms of public health,” Balmes said.

Plastic’s uncertain future

Ponder this as more Texas coastal land is consumed by industry:

What if the markets for petrochemical products, particularly plastics, are shrinking? What if much of this development is for naught? On Corpus Christi’s Refinery Row, for example, the Corpus Christi Polymers plant — conceived to make polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, a type of polyester found in fabric and single-use bottles — sits unfinished. Is it a harbinger of an industry pullback? The company did not respond to requests for comment.

The American Chemistry Council, the chemical industry’s main lobbyist and booster, acknowledges a slackening. “Economic sentiment for U.S. chemical manufacturers hit a rough patch in [third quarter] 2025, as companies grappled with softening demand and economic headwinds,” the council said in its latest Economic Sentiment Index. It did see a “flicker of optimism” for late 2025 and early 2026.

But some independent analysts are more doubtful.

“Already in a downcycle, the ethylene industry faces unprecedented challenges,” Wood Mackenzie, a market-research firm, reported last year. “Our analysis shows that a third of steam crackers globally are at some risk of closure over the next five years.” Ethylene producers, especially in Europe and Asia, faced “considerable overcapacity” and declining profitability, the firm said.

“The industry is panicked,” said Mike Belliveau, founder of Bend the Curve, a nonprofit research institute that promotes alternatives to petrochemicals and plastics. “All the industry pundits say this is not a normal cycle.” The reasons, Belliveau said, include growing public rebellion against plastics and mounting anxiety over climate change. Uncertainty is rising despite the Trump administration’s efforts to promote fossil fuels, ignore the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement and undermine a proposed global treaty to address plastic pollution.

Asked for comment, an American Chemistry Council spokesperson said he had nothing to add to the Economic Sentiment Index. The group’s state counterpart, the Texas Chemistry Council, didn’t respond to interview requests from Public Health Watch.

The industry is panicked. All the industry pundits say this is not a normal cycle.

mike belliveau, founder of bend the curve

In an October news release, however, the Texas council exuded confidence: “The business of chemistry in Texas will remain a global leader — driving innovation, creating opportunity, and improving lives across our state and beyond.”

Last month, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott announced that Formosa Plastics Corporation will invest $150 million in a plant in Jackson County, about 100 miles southwest of Houston, that will make a chemical feedstock known as C6, or 1-Hexene. The project qualifies for a state economic incentive program and “will grow good-paying jobs for Texans, expand economic opportunity in Jackson County, and further our state’s manufacturing leadership,” Abbott said.

The governor did not mention some complicating facts:

1-Hexene is extremely flammable, can irritate the eyes and respiratory tract and is toxic to aquatic organisms. High concentrations, the International Programme on Chemical Safety reports, can cause “a deficiency of oxygen with the risk of unconsciousness or death.”

The Formosa Plastics complex in Point Comfort, which will use the chemical, paid $50 million in 2019 to settle a lawsuit claiming it had illegally dumped billions of plastic pellets into Lavaca Bay and nearly $3 million in 2021 to settle Clean Air Act violations alleged by the EPA.

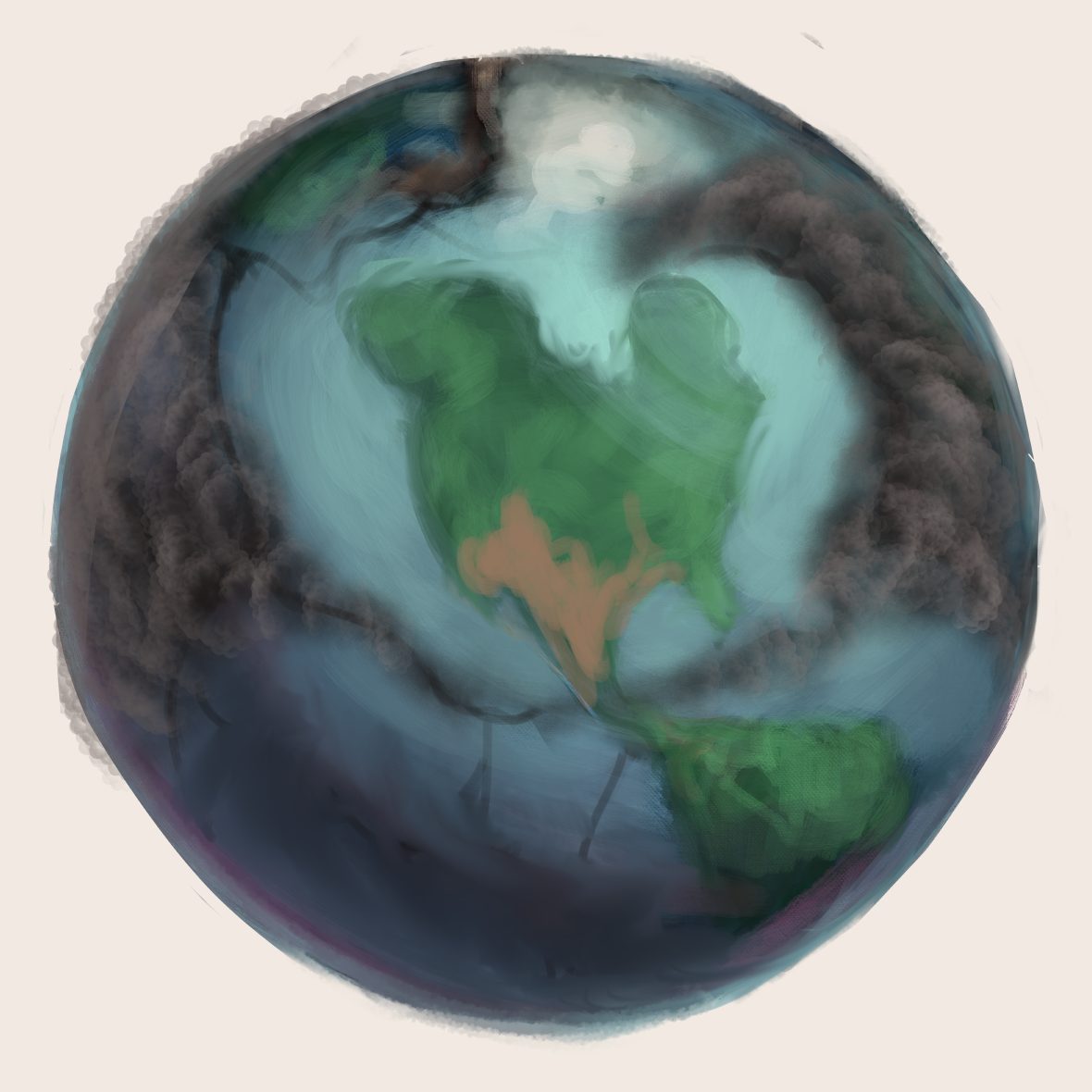

Texas’s colossal carbon footprint

With drilling rigs penetrating the methane-rich Permian Basin in the west and chemical manufacturing plants spewing carbon dioxide in the east, Texas released almost 2 trillion pounds of greenhouse gases in 2021, according to a TCEQ report. That’s more than what was released that year by energy-rich Saudi Arabia, a country three times the size of Texas, or by the 100,000-plus tankers, bulk carriers and container ships that move 80% of internationally traded goods by volume.

The planet-warming pollution could swell. A 2024 report by the Center for International Environmental Law, or CIEL, found that the U.S. petrochemical boom would boost the nation’s greenhouse-gas emissions by 38%. Texas would be responsible for almost half of the increase.

Barnaby Pace, a CIEL senior researcher, said that plastics production — a primary application of petrochemicals — is one of the few fossil-based industries in growth mode.

“There’s very scary projections out there,” Pace said. “There was a study last year from Lawrence Berkeley National Labs that said that if the plastic production market keeps growing, it would use 25% of the remaining carbon budget.” That means it would consume a quarter of the planet’s greenhouse-gas allotment under the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the Lawrence Berkeley paper estimated.

According to Oil & Gas Watch data, Texas has issued draft and final permits that authorize nearly 38 billion pounds of greenhouse-gas emissions from 14 new petrochemical projects in the past three years. That equates to emissions from 45 natural gas-fired power plants. (The state is among the nation’s leaders in power generation from two forms of clean energy, wind and solar. The Trump administration has sought to dampen enthusiasm in both).

CIEL also looked at lifecycle emissions — pollution that starts when natural gas is extracted, continues during chemical production and transportation, and ends in a landfill or a farm field. CIEL determined that ammonia plants had some of the biggest climate impacts. Ammonia is primarily used to create fertilizer, which, as it decomposes on fields, generates nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas about 270 times more potent than carbon dioxide. (By comparison, methane, unleashed during oil and gas extraction, is about 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.)

Twenty ammonia-related projects are planned or have been announced in Texas, Oil & Gas Watch says, with most slated for Jefferson and Harris counties.

County judge stands by petrochemicals

Jefferson County

Jefferson County Judge Jeff Branick is open to changing his mind.

Elected to the county’s top executive office as a Democrat in 2010, Branick switched parties six years into his tenure. He was once a personal-injury lawyer representing workers exposed to toxic substances at the dozens of chemical and synthetic rubber plants in the county. Now he’s a champion of the petrochemical industry. He and his colleagues on the Commissioners’ Court have approved millions of dollars in tax abatements to attract its business.

“I will tell you that the industry as it existed when I was a little boy is probably not something I would be in favor of today,” said Branick, 67, who was born and raised in Port Arthur. “The air was palpable, the smell was ever present, the water was polluted.”

Branick said that air quality in Jefferson County has improved markedly; indeed, the county violated the EPA standard for ground-level ozone from 1992 to 2009 but has complied with that rule for the past 15 years. State data show that industrial facilities’ emissions of ozone-forming nitrogen oxides and VOCs have been in steady decline since 2010. While the county is still one of the nation’s largest sources of 1,3 butadiene and ethylene oxide, releases of those carcinogens have also fallen in recent years, according to EPA data.

Some pollutants are on the rise, however, including particulate matter, carbon monoxide and ammonia. Five ammonia plants are planned in the county.

EPA data show that the county is the nation’s second-largest contributor of greenhouse gases from stationary sources like chemical plants. Pending petrochemical development could boost that amount.

Nonetheless, Branick sees the industry as a critical resource for the rest of the country.

“They make the constituent ingredients for virtually every consumer product made in the United States, from the interiors of your car to the tires on your car,” he said. “Paints, surfactants, baby diapers, Dawn dishwashing detergent, Tide clothes-washing detergent, a lot of things that are used in the electrical industry, and, of course, the plastics industry.”

Branick said that while tax abatements result in some lost revenue, the industry still accounts for about two-thirds of the county’s property-tax proceeds. When plant workers spend money locally, the economy benefits, he said, especially the retail and hospitality sectors.

I will tell you that the industry as it existed when I was a little boy is probably not something I would be in favor of today. The air was palpable, the smell was ever present, the water was polluted.

jeff branick, jefferson county judge

Economic studies commissioned in other parts of the state by the Texas Campaign for the Environment suggest that tax abatements — foregone revenue — aren’t a good deal for school districts and local governments. The consulting firm Autocase found that abatements granted in Harris, Brazoria and Calhoun counties and the Coastal Bend region dating to 2012 have totaled nearly $6 billion. The average “cost” of a permanent petrochemical industry job ranged from $781,000 in Calhoun County to $2 million in Brazoria County, Autocase concluded. The firm is working on a similar study in Jefferson County.

Nor has the industry-generated wealth been shared equally. Census data show that the poverty rate in Beaumont-Port Arthur has increased since 2021. Jefferson County still has one of the highest unemployment rates in the state.

One-third of Jefferson County residents are Black, the highest percentage in the state. Its economic and educational disparities are striking: Census data show that the county’s predominately white cities — Nederland, Port Neches and Groves — are near or below the state poverty rate of 13.4%. Poverty rates in the predominantly Black cities of Beaumont and Port Arthur are 19.9% and 29.1%. This year, the Texas Education Agency gave “D” rankings to school districts in Beaumont and Port Arthur and “B” grades to those in Nederland, Port Neches and Groves. In early December the state announced that it would take over the Beaumont Independent School District due to its “unacceptable” rankings.

Branick acknowledged that some petrochemical companies have been slow to hire Jefferson County residents. “One of the things I’m working on right now is making sure that these global corporations that come in to build projects utilize local vendors, contractors and suppliers so that we can improve permanent job placement,” he said. “But there’s also a problem in our county that relates to a lack of qualification, either because of substance-abuse disorders or lack of furthering education through technical or vocational training, which we have an abundance of opportunity for …”

The judge said he had not heard projections of increased air pollution associated with the petrochemical building boom but trusts the TCEQ to vet each permit and assess the public health impact.

“They have industrial hygienists and toxicologists and epidemiologists on their staff,” he said. “We don’t have any with the county.”

Three septuagenarians step up

Jefferson County

Terry Stelly fell in love with biology when he was in second grade and received a microscope as a Christmas present. He was born and raised in Southeast Texas, which is rich in biological life. Just north of his childhood home in Beaumont was a swath of land that would become the Big Thicket Natural Preserve — a convergence of nine ecosystems and nearly 2,000 species of plants and animals. To the south was the Gulf of Mexico.

Stelly got his bachelor’s degree in marine biology and his master’s in biology at Lamar University in Beaumont, where Dr. Richard Harrel, president of the advocacy group Southeast Texas Clean Air and Water Inc., became his mentor. Stelly joined the group in a bid for extra credit, and spent the next four decades petitioning the state for better environmental protections in Jefferson, Hardin and Orange counties. He worked as a biologist for the Sabine River Authority and, later, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, for nearly 40 years.

Now retired, Stelly has taken over as president of the environmental group. While membership has dwindled from dozens of people to six, his commitment to the cause hasn’t been shaken.

Stelly is among the few who regularly challenge petrochemical permits in Jefferson County. He analyzes pollution data and combs through dense TCEQ permit applications. “Sentiment,” he said, “doesn’t get you anywhere” without hard numbers.

He submits written comments to the agency as often as he can. In the case of Woodside Energy, he asked that the state deny the ammonia plant’s permit unless it reduced its proposed emissions of fine particles and other contaminants by 25%. In the case of Energy Transfer, Stelly argued that greenhouse-gas emissions from the ethane cracker would be “excessive,” and implored the company to use better technology or low-carbon fuels.

His arguments failed to derail Woodside and almost certainly won’t stop Energy Transfer.

We continue to pay, and they’re making billions.

ellen buchanan, member of sierra club’s golden triangle group

Stelly has a novel idea: “Why not ask people to do better than their permits?” This concept, he knows, is unlikely to gain traction in Texas. But he presses on, working with two members of the Sierra Club’s Golden Triangle Group, Ellen Buchanan and Mary Bernard, to muster some resistance to the buildout. The three septuagenarians have filed more than 30 formal comments or requests for public meetings or hearings with the TCEQ in the past five years.

“Nothing ever happens, though,” Buchanan said. “We do our comments and [the companies] still get their permit.” She, Stelly and Bernard have begun appealing directly to those companies; whether this will have any effect remains to be seen.

According to its 2025-2026 budget, Jefferson County is riding a $22 billion wave of petrochemical plant improvements. “In addition,” the document says, “hundreds of millions of dollars are being spent on terminal and pipeline facilities to support these projects … In total, announced expansion projects in our county exceed $65 billion.”

Buchanan finds it off-putting that the county and its school districts are subsidizing some of this development when the region is already attractive to the petrochemical industry due to its robust infrastructure and coastal access.

“We continue to pay,” she said, “and they’re making billions.”

An outlier amid the boom

Nederland, Jefferson County

On a rainy Thursday night in November 2023, a week after Thanksgiving, Matthew Kennedy slogged through a flooded parking lot outside the Nederland Performing Arts Center. He was headed to a TCEQ public meeting on a plastics plant planned just outside the city of about 18,500, within a few miles of 15 schools.

“I just thought that was so inappropriate that they moved forward with the meeting,” Kennedy said.

He had spent the previous two weeks reaching out by text to roughly 5,000 Nederland residents as part of his work with the Texas Campaign for the Environment. Kennedy said most of the dozens of people he spoke with had not heard anything about Energy Transfer’s proposed ethane cracker. If they wanted to learn more or submit formal comments, they’d have to fight their way through a downpour.

Energy Transfer — the multibillion-dollar company behind the controversial Dakota Access Pipeline — had applied for a TCEQ permit to make ethylene, a key ingredient in plastics. The permit would allow the Dallas-based company to release millions of pounds of ozone precursors and carbon monoxide. This would make the plant one of the largest sources of petrochemical pollution in the state, Texas emissions data show.

According to comments submitted by environmental lawyers at the time, the company’s own analysis estimated that people living 17 miles away from the cracker would be impacted by air pollution at a “significant level.” The facility’s greenhouse-gas emissions could rival those from a dozen natural gas-fired power plants.

The TCEQ did not provide these details at the Nederland meeting in 2023 or in the public notice beforehand. Instead, when permit reviewer Cara Hill took the microphone, she raced through an overview filled with technical jargon and lacking details. “The facility is expected to be protective of the environment and human health,” Hill said, reciting a rote phrase typically used in permit approvals.

Listen to the one-minute presentation:

In 2022, a month after Energy Transfer submitted its permit application to the TCEQ, the Nederland Independent School District granted the company a $121 million tax abatement.

Now, the TCEQ is in the final stages of deciding whether to approve the ethane cracker.

Lone Star Legal Aid attorney Chase Porter represents two people and two organizations that have formally opposed the plant by requesting a contested-case hearing. He wants the state to address deficiencies he and other lawyers identified before it issues a final permit to Energy Transfer.

The draft permit, Porter said, showed that almost all of the facility’s equipment would be operating without Best Available Control Technology, a legal requirement for major sources of air pollution. This could lead to unnecessary emissions of pollutants like carbon monoxide, VOCs and particulate matter, and the plant could “significantly degrade air quality,” he and a lawyer with the Environmental Integrity Project wrote to the TCEQ.

Shortly after the 2023 public meeting in Nederland, the EPA strengthened its standard for particulate matter, and the ethane cracker would have violated the new standard. Energy Transfer agreed to change its permit application.

Porter was glad to see that in its amended application, the company had removed from the project one of the largest emitters of particulate matter. But Energy Transfer had also made changes to its pollution calculations that raised red flags, he said.

Major sources of air pollution must conduct a detailed air-quality review if a project’s estimated emissions will be above what the EPA calls a “significant impact level.” This is meant to ensure that a project doesn’t violate standards.

Porter said that Energy Transfer’s first application used a higher threshold than what the EPA recommends. Still, the company projected that its fine-particle emissions would exceed even that benchmark, triggering the air-quality review.

In its second application, Energy Transfer increased the threshold again, this time avoiding the review. In effect, it moved the goalpost.

There was another wrinkle in Energy Transfer’s calculations.

The company now says that particulate pollution from some of the largest remaining pieces of equipment at its Nederland cracker will be half of what was originally expected. Engineers use emission factors to estimate the amount of pollution released by each piece of equipment at a plant. Energy Transfer chose a factor that was significantly lower than what the EPA recommends, the Environmental Integrity Project wrote in comments to the TCEQ. A lawyer with the group said Energy Transfer did not provide enough information to the state to determine whether that decision was appropriate.

Public Health Watch tracked down the origin of the emission factor used in the company’s calculations. It came from the testing of a natural-gas boiler more than 300 times smaller than the ones that will be in the Energy Transfer cracker. The company applied this factor not only to different equipment types — boilers, heaters and furnaces — but also to different fuel types.

“It would not be appropriate to use this emission factor for estimating emissions used in modeling anything besides particulate matter emissions from a natural gas fueled boiler,” Jill Inahara, an environmental engineer with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, wrote in a statement to Public Health Watch. The department developed the factor 30 years ago.

Porter said the Energy Transfer permit “will test the [TCEQ’s] willingness to scrutinize what the applicant’s providing them and test whether the agency is willing to make that hard decision to say, ‘We can’t allow this.’”

In comments to the TCEQ in October, Porter and the Environmental Integrity Project argued that in light of substantial changes Energy Transfer made to its application, the TCEQ’s own rules call for reopening the public comment period. However, state records show the agency approved of the company’s changes to the application this year and has moved on to one of the last steps in the permitting process. The TCEQ’s executive director is expected to decide soon whether to recommend approval; after that, the agency will decide whether to grant any contested-case hearing requests.

I think this is really a permit that will test the [TCEQ’s] willingness to scrutinize what the applicant’s providing them and test whether the agency is willing to make that hard decision to say “We can’t allow this.”

chase porter, senior attorney with lone star legal aid

The TCEQ spokesperson wrote in an email to Public Health Watch that it “reviewed the [Energy Transfer] application and verified the proposed project is protective of human health and the environment and no adverse effects are expected to occur.” It did not respond to questions about the likelihood of a second public meeting. The spokesperson said that the project complied with Best Available Control Technology requirements and declined to answer questions about whether the agency condoned Energy Transfer’s use of the Oregon emission factor.

The Trump administration has asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to reverse the EPA’s new standard for fine particles. If that happened, Energy Transfer’s proposed ethane cracker would not be at risk of violating the standard and the company’s permit calculations for particulate matter would become moot.

Public Health Watch reached out to Energy Transfer six times over three weeks by phone and email, sending lists of questions. The company did not respond to any of these requests.

A sprawling, sometimes-disruptive neighbor

Baytown, Harris County

Exxon Mobil’s oil-refining and chemical-manufacturing complex in Baytown, 25 miles east of downtown Houston, covers 3,400 acres, a footprint four times that of New York’s Central Park. The company has been filling in that space for more than a century, announcing this year that again it wants to increase the capacity of its twice-expanded Olefins Plant, which opened in 1979 and makes ethylene, propylene and 1,3-butadiene. The chemicals are used in the production of plastics, synthetic rubber and other products.

People in Baytown, a city of 86,000, have a complicated relationship with the fossil-fuel titan. Exxon Mobil’s Baytown complex pays more than $100 million a year in taxes, contributes “over $7 billion to the region annually” and supports “nearly 15,000 direct and indirect jobs,” the company says. Not to mention the $1 million it donates annually to local nonprofits and the thousands of volunteer hours its employees and their families devote to schools, nature centers, nursing homes and food banks.

Some residential areas of the city would not look out of place on Houston’s affluent west side. Hotels, restaurants and other businesses have sprung up near Interstate 10.

Those are the positives.

The negatives: air and noise pollution and the occasional house-shaking explosion. In December 2021, a refinery pipeline leaked naphtha, a flammable hydrocarbon mixture, triggering a fire and a thundering blast. A lawsuit filed by the Texas Attorney General’s Office alleged that at least 7,496 pounds of cancer-causing benzene and other chemicals were illegally released during the event. Some Baytown residents and Exxon Mobil contractors said they sustained injuries ranging from severe burns to hearing loss.

Then there was the 15-year legal battle between Exxon Mobil and two environmental groups representing a handful of their Baytown members. A citizens’ lawsuit filed in 2010 alleged that the Baytown complex had committed more than 16,000 violations of the Clean Air Act over eight years — an average of more than five violations per day. Facing more than $14 million in fines, Exxon Mobil kept losing in court and kept appealing, ultimately to the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to take the case and ended the saga last June.

I’m not against Exxon — Exxon has provided a good living for a lot of people. I just wish they were cleaner and more self-aware.

Augustín Loredo III, vice president of the West baytown civic association

Finally, a Public Health Watch analysis found that the ever-growing Olefins Plant has reported 239 unplanned air releases to the TCEQ since 2003. Among them: a two-day flaring event in April that discharged more than 90,000 pounds of pollutants. The plant released more benzene during that event than it did in all of 2024, EPA data show. It’s unclear if the company will be penalized for the episode.

Augustín Loredo III reflects the dichotomy of life in Baytown. He was born in the city, as was his late father, Augustín Jr., who worked on an Exxon Mobil tanker for 21 years. He is married with four children, three of them grown. He teaches Mexican-American studies and Spanish and coaches boys’ soccer and cross-country at South Houston High School. He lives on Carolina Avenue, next door to his mother, Leonila, less than a mile from the Exxon Mobil complex’s south gate.

“Part of me wants to leave,” said Loredo, 51. “But I can’t leave. Mom is still here.”

Loredo is not a disengaged citizen. He serves on Baytown’s Planning and Zoning Commission and is vice president of the West Baytown Civic Association. He appreciates Exxon Mobil’s economic contributions but doesn’t hesitate to criticize the company when he believes it has done something wrong. Too often, he said, it’s allowed to pay fines instead of fixing systemic problems, a situation he likens to “enabling kids.”

“I’m not against Exxon — Exxon has provided a good living for a lot of people,” Loredo said. “I just wish they were cleaner and more self-aware.”

Theresa Blackwood lives on Galveston Bay, about a half-mile from the Exxon Mobil complex’s western edge and two miles from the Olefins Plant, which she calls the “eight-headed dragon,” a reference to its eight newest ethane steam cracking furnaces.

“It’s so intrusive,” said Blackwood, 59, a business consultant. “It took over a wooded area and has really affected the lives of hundreds and hundreds of residents.”

Vibrations from the plant have damaged homes, including her husband’s. Odors can be intense, and Blackwood logs them religiously. She wishes the TCEQ’s permitting process were less opaque and Exxon Mobil were more communicative when there’s an incident. She knows the oil giant won’t pick up and leave — she merely wants it to “do the right thing.”

Exxon Mobil did not respond to requests for comment.

Demanding transparency and documenting risk

Houston, Harris County

Operating in heavily industrialized, predominantly Latino eastern Harris County, Yvette Arellano, founder and director of the grassroots organization Fenceline Watch, and colleague Shiv Srivastava have tried for five years to make the TCEQ’s permitting process more equitable and transparent. They’ve had limited success. Translation services are now required at many agency public meetings and permit hearings. But meaningful public notice for those gatherings is often lacking, Arellano and Srivastava said in an interview.

The TCEQ tends to post meeting notices in small, Spanish-language news outlets instead of larger outlets like the Houston Chronicle, Univision 45 or the newspaper El Perico, Arellano said. The result is weak turnout, even when public safety is clearly at risk, she said.

On September 30 and October 1, for example, the TPC Group, which makes butadiene and other chemicals at its plant in Houston’s East End, hosted meetings at Cesar E. Chavez High School. The company’s aim was to reassure nearby residents that it had made safety improvements since a sister facility in Port Neches blew up in 2019. That explosion injured five workers, caused more than $150 million in offsite property damage and was felt 30 miles away.

Last year, TPC Group pleaded guilty to federal Clean Air Act violations and agreed to pay more than $30 million in criminal fines and civil penalties for what the Department of Justice called an “entirely preventable” catastrophe in Port Neches. The company withdrew from the plea agreement in January after a judge ordered an additional $292 million in restitution for blast victims. In a statement, TPC said it disagreed with the court and “exercised its right to withdraw from the plea agreement.”

In December 2024, TPC Group completed an expansion of its Houston plant. Fenceline Watch had failed to convince the TCEQ to deny a permit for the project, noting that the plant was a repeat violator of the Clean Air Act and the state itself had sued TPC Group over the Port Neches explosion, which resulted in a $12.6 million settlement. “If they were willing to sue and then allowed [TPC Group’s] permit to get renewed, that’s some kind of dissonance,” Srivastava said.

He and Arellano said they weren’t notified of the September 30 meeting at Chavez High School even though the TCEQ had representatives at the meeting and knew Fenceline Watch was an interested party. They learned of the next evening’s meeting only after a community member texted them. When they got there, they counted no more than a dozen East End residents in the audience. Two attendees who live within a mile of the plant complained they had heard about the meeting from neighbors, not the TCEQ, Arellano said.

To demonstrate what’s at stake, Arellano and Srivastava went in October to the Bob Casey U.S. Courthouse in downtown Houston to view documents outlining worst-case accident scenarios prepared by the owners of 10 petrochemical facilities in eastern Harris County. Such documents must be accessed in person and can’t be copied or photographed; researchers can only take handwritten notes.

What they found was sobering. TPC Group, for example, said a vapor-cloud explosion at its Houston plant could release nearly 11 million pounds of butadiene, which can cause acute health effects ranging from throat and eye irritation to blurred vision and fainting. Chronic exposures can cause cancer. The cloud, TPC Group estimated, could travel 1.8 miles and affect 39,000 people. “Receptors” would include schools, residences and major commercial and industrial sites.

A Public Health Watch review of EPA data found that the company’s Houston plant has been in noncompliance with the Clean Air Act for at least the past 12 quarters. There were “significant violations” in each of those quarters, the data show. The facility has been fined a total of $553,738 by the TCEQ for alleged clean-air violations since 2019, EPA data show.

TPC Group did not respond to requests for comment.

A ‘perfect storm’ for environmental injustice

Robert Bullard, who turned 79 on December 21, is known as the “father of environmental justice” and has been a leader in that movement for decades. But this moment seems unique even to him.

This, Bullard said, is because Texas’s petrochemical buildout, combined with the Trump administration’s dismantling of environmental regulations, has created the “perfect storm” for intensifying pollution and, by extension, illness, in communities that are already suffering.

A recent report from Texas Southern University in Houston, where Bullard is the director of a namesake environmental and climate justice center, found that 90% of the planned petrochemical expansions and new facilities researchers examined are in communities with more people of color or people living in poverty — or both — than national and state averages. More than three-quarters of these projects are in communities with higher levels of fine-particle pollution than the national average. And 84% have above-average emissions of toxic chemicals.

The added pollution will only deepen racial and economic disparities in these places, Bullard said.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has dissolved community protections, including EPA grants dedicated to grassroots environmental-justice groups. The Trump EPA also announced it is “reconsidering” rules from the Obama and Biden administrations meant to reduce hazards associated with facilities that handle extremely explosive and toxic chemicals. Eighty-three percent of Texas’s planned petrochemical expansions and new facilities are in communities in closer proximity to these high-risk facilities than the national average, according to the TSU report.

Bullard and his team at TSU are responding to the chaos by feeding data to communities bordering industrial plants so they can fight for themselves.

“Having the government cancel the grants does not cancel our movement, and it does not cancel the work that we’re doing,” Bullard said. “If we marry that science, research, data and facts with action, that’s our movement for environmental and climate justice.”

‘Small wins’ for the public

For decades, Air Alliance Houston has tried to help ordinary people navigate the seemingly impenetrable TCEQ permitting process.

The group created Air Mail, an interactive online map that updates regularly with new permit applications or renewals. The tool shows deadlines for public engagement; links to comment forms and facilities’ profile pages on the TCEQ’s website; and contact information for local elected officials. Air Alliance also sends postcards to people in affected neighborhoods.

Genesis Granados, the group’s environmental justice program senior manager, works mostly with communities of color and people with limited English proficiency in Houston’s industrial areas.

Apart from odors and occasional flares, petrochemical pollution in these areas is largely invisible, so it can be hard to convey risks to residents, Granados said. Loyalty to plants that provide stable, relatively high-paying jobs can be hard to penetrate, and some residents fear retaliation for speaking out.

That means success has to be graded on a curve.

“Our strategy has been stalling, stopping or strengthening” permits, Granados said. “It’s a small win, but stalling a permit means that [the company] can’t function.”

Money can also change minds. People who might otherwise side with the industry have been surprised to learn that billion-dollar companies are receiving taxpayer subsidies, in some cases at the expense of school funding, Granados said. “That has also generated movement within parents because they’re realizing like, ‘OK, let’s really talk about how petrochem is actually affecting all levels of our community, not just environmentally.’”

Sometimes, the companies and the agencies are expecting that there won’t be a fight, and when there is one, we’ve seen change happen.

michael esealuka, petrochemical coordinator with break free from plastics

National and international organizations are mobilizing in Texas as well. Break Free from Plastics, an advocacy group that seeks to stop plastic production and pollution, offers technical advice on permitting to members in the state and in Louisiana. It hosts webinars on how to track unlawful pollution events, read permits and estimate the impacts of emissions.

“Sometimes, the companies and the agencies are expecting that there won’t be a fight, and when there is one, we’ve seen change happen,” said Michael Esealuka, the group’s petrochemical coordinator.

Here are some examples of recent Texas petrochemical projects that were put on hold or canceled due in part to community engagement:

- Exxon Mobil’s plastics plant paused: Calhoun County resident Diane Wilson sued her local school district this year after catching a Texas Open Meetings Act violation related to the school board’s approval of a tax abatement for Exxon Mobil’s $10 billion Coastal Plain complex. Advocates think her lawsuit and the resulting community outcry played a role in the company’s pausing its plans a few months later. Exxon Mobil cited market changes in its announcement.

- Desal plant in Corpus canceled: The Corpus Christi City Council voted down a proposed $1.2 billion desalination plant meant to supply water to the city’s growing petrochemical sector. Opponents criticized the ballooning cost and worried that the plant’s saltwater waste would disrupt ecosystems.

- Ammonia plant objectors receive contested-case hearing: The TCEQ granted a contested-case hearing to members of the Coastal Watch Association who opposed Enbridge’s plans for a new industrial complex in San Patricio County, just north of Corpus Christi. The plant, called “Project YaREN,” would produce and export “blue” ammonia, a “low-carbon” version of ammonia that is used in fertilizer and is a prospective fuel. The state held a preliminary hearing this month, granting “affected party” status to members of the organization and extending the case until next spring.