RIO GRANDE VALLEY, TEXAS — In this roughly 100-mile stretch of citrus groves and palm-fringed neighborhoods along the Mexican border, a preventable disease continues to take an outsize toll on Latina women.

Every year in the Rio Grande Valley — where more than 90% of residents are Hispanic and more than a quarter live in poverty — at least 75 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer on average each year, according to data from the National Cancer Institute. About two dozen die from it annually.

The rates of new cases and deaths in the four-county area are anywhere from about 40% to 80% higher than the national rates, depending on the county, according to the institute’s data. Across Texas, Hispanics have a 28% higher rate for cervical-cancer incidence than all residents, the latest Texas Cancer Registry data show.

The numbers evoke pain and frustration among health experts and patients. An effective vaccine against the human papilloma virus, which causes the cancer, has been around for almost two decades. Screening makes it possible to detect and remove precancerous cells before the disease develops.

“Nobody should get a cervical cancer diagnosis or die from it,” said Melissa Lopez Varon, a cancer epidemiologist at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

National studies point to several culprits, including lack of knowledge about the value of screening and vaccines, high rates of people lacking health insurance, and, in some areas, a shortage of providers. These factors play out in the Rio Grande Valley as they do in the rest of Texas, researchers and clinicians told Public Health Watch. The state’s vaccine-completion rate against HPV, for instance, is below the national average — 57.5% versus 61.4% of teens aged 13 to 17.

The risks can distress even those who have access to care and screening. Maria, 24, who asked that her last name be withheld, is a vocational nurse who lives in Brownsville. On February 17, she had her annual wellness exam, including a pap smear, which can identify abnormal cells in the cervix that may indicate cancer or growing lesions that precede the disease.

A few days later, when she was at work, she got an email saying her results were ready. “I wasn’t actually expecting something bad,” she said. When she saw she had abnormal results, “the shock hit me. I wanted to cry.”

Breaking the news to her father, who lives in Mexico where she grew up, was especially hard. He lost his mother to uterine cancer when he was 11.

Maria is also a mother. “I think of my little one. I don’t want to leave him,” she said.

Vigilance is key

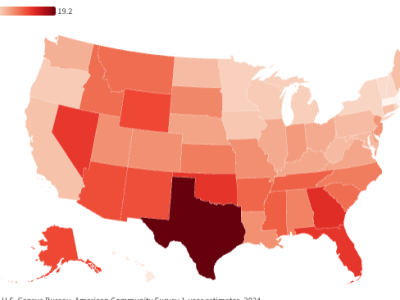

Texas has the fourth highest cervical cancer rate in the nation, with 9.6 cases per 100,000 people compared with 7.5 for the U.S., the National Cancer Institute reports. The state has the 6th highest rate of late-stage cervical cancer, meaning the disease has spread to other parts of the body and chances of survival five years after diagnosis drop significantly.

The Rio Grande Valley is among the most burdened regions of Texas for cervical-cancer cases, late-stage diagnoses and deaths. Hidalgo County, for instance, has the 7th highest incidence rate of late-stage cervical cancer in Texas. Starr County ranks 10th worst in overall incidence, and Hidalgo and Cameron counties rank 6th and 7th in death rates. Data isn’t available for smaller Willacy County.

Several risk factors linked to cervical cancer converge in the region. The area is rural or partially rural and medically underserved for primary care, according to federal data. Uninsured rates are high, ranging from 22% to 30% of people under age 65 in the four counties, the Census Bureau reports; Texas is one of 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid to cover more low-income adults. The region reflects a national disparity for Latina women, who have higher rates of cervical cancer, often because of lack of health insurance and paid sick leave, language barriers and educational inequities, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states.

The limited access to affordable care stands out for many experts. In Texas, 27.5% of non-elderly Hispanic people are uninsured, totaling over 3 million, according to 2023 census estimates. Texas’s uninsured rate is 18.7%.

Lacking health insurance “doesn’t cause cervical cancer, but it’s the main barrier to early detection and timely treatment,” said Belinda Reininger, a doctor of public health and a professor at the UTHealth Houston School of Public Health in Brownsville.

That’s because cervical cancer prevention depends on regular doctor’s visits, she said. Even women who have received the vaccine need periodic screening to check for any abnormal growth. The vaccine does not guard against all strains of HPV linked to cervical cancer and, in rare cases, a person may develop the disease without infection by the virus.

When screening reveals abnormal cells, doctors recommend a series of follow-up procedures to reach a diagnosis and weigh any treatment. Patients who don’t have a medical home or are afraid out-of-pocket costs may skip or delay the care.

Dr. Rose Gowen, a retired obstetrician-gynecologist and now a faculty associate at UTHealth Houston School of Public Health in Brownsville, said many women only visit doctors when they are pregnant — to take advantage of temporary Medicaid coverage. “We kind of hop along with their pregnancies,” she said.

Alondra Rodriguez, a promotora de salud, or community health worker, who works with Planned Parenthood’s Habla Con Tu Hermana team, said many women tell her things like: “I haven’t had my pap smear since my son was born, and he’s 25 years old.”

Prevention often gives way to more pressing needs, said behavioral epidemiologist Jane Montealegre at MD Anderson Cancer Center. “They’re coming in for chronic disease management and other urgent issues … Preventive care isn’t always on the list,” she said.

***

Maria received the HPV vaccine three years ago — but that didn’t quell her urgency after learning the test results. She set up appointments over two months.

She had a colposcopy, an imaging procedure that takes a closer look at the cervix. She underwent a loop electrosurgical excision procedure, or LEEP, that removes abnormal tissues. Some of the tissue would be biopsied to check for cervical cancer.

Maria wanted answers, but found the process challenging. The LEEP, for example, has a small risk of scarring the cervix, which could lead to future pregnancy complications.

That possibility, though slight, frightened her, but she and her husband “have to think of the [child] we have and not the ones we might not have,” she said.

The risks of doing nothing

Even when people are screened, they may not proceed with a colposcopy, a LEEP and cancer treatments. Nationally, more than 20% of women in the U.S. whose test results are abnormal do not get follow-up testing or treatment. As many as 40% of cervical cancer diagnoses occur in women who received an earlier abnormal screening result but did not remove precancerous tissues in time.

Lopez Varon, the MD Anderson epidemiologist, recalls speaking with Valley clinicians who had asked their patients with cervical cancer whether they had ever had a pap smear. Often “they did … but nobody did anything about it,” she said.

Lost time can mean life or death. A woman diagnosed early has a 91% likelihood of surviving the next five years, but the odds drop to 19% with a late-stage diagnosis.

In the Rio Grande Valley, promotores play a crucial role in guiding women through the health-care system to avoid these outcomes. Marisol Medina, of the Habla Con Tu Hermana program, goes door to door in communities, including impoverished colonias, to offer help and information. She and colleagues hold community events and house parties. They talk with people of all ages about sometimes taboo subjects, such as sexual and reproductive health. They know some women are uncomfortable with the prospect of a pelvic exam, which is needed to obtain a pap smear. Some of them say their partners or husbands won’t allow it. Promotores help families understand the necessity of these procedures and how to access care.

“We see the challenges that come up every single day,” said Medina, who’s been with the Hermana program for nine years.

Among the points she makes to families is that they have options even with little or no health insurance, such as services from Planned Parenthood and federally qualified health centers. There may be no cost to see a doctor. People are often so worried about medical bills that they don’t take advantage of existing programs that will cost them nothing. “Not knowing the cost,” Medina said, becomes a barrier in itself.

Promotores are also practical problem solvers. Medina and her colleagues help women find transportation to get to their appointments and may accompany them to the doctor’s office. Promotores also connect people with rent assistance programs and food banks. Medina takes pride in her work and thus feels frustration when she can’t find a solution. She’s seen some women decide not to pursue more serious treatment even after receiving a cancer diagnosis. “That is one hard part, as a promotora … We want to do so much more but we are limited as well,” she said.

Advances and setbacks

The fight against cervical cancer in Texas is nearly at a standstill.

Over a decade, through 2022, the rate of new cases has remained the same, at 9.5 per 100,000 population. The death rate has barely budged, at 2.8 for 2018-2022.

The pattern is similar nationally, with studies showing the incidence rate among women aged 20 to 24 has declined, thanks to the vaccine, but the rate for those aged 30 to 44 has risen.

In the Valley, several efforts aim to improve health-care access to address cervical cancer. Lopez Varon co-directs a project that trains more clinicians in providing care for patients, including how to perform the excisional procedure. A decade ago, when that work began, there were no providers at federally qualified health centers that offered the procedure.

Montelaegre co-leads a program providing HPV vaccination in area middle schools and is introducing self-testing kits that allow women to do their own screening in a clinic. The FDA’s recent approval of at-home kits could also help more women receive screening.

Some projects benefit from state funding through the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas. That agency, which has received $6 billion in state funds since 2007, supports research and prevention programs. Grantees provide screening and diagnostic services to people who participate in prevention projects.

A joint state-federal program, the Breast and Cervical Cancer Services Program, funds federally qualified health centers to provide care and services to the uninsured. Patients who receive a cancer diagnosis may qualify for Medicaid to cover their treatment. The program is the Texas branch of a nationwide initiative.

Nurse practitioner Laura Guerra, who works at the federally qualified health center Su Clínica in Brownsville, said the two programs allow her and colleagues to care for many uninsured and underinsured women for free. “Without this, I don’t know what these women would do,” Guerra said.

But progress has come with struggles. In 2013, Texas created the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, with its School of Medicine, to help address the region’s provider shortage. But in 2022 it lost its partnership with the for-profit, physician-owned system DHR Health to host medical residencies.

Many patients with cervical cancer lack easy access to a specialist. There are only two gynecological oncologists in the Valley, and both work at DHR Health.

Texas’s strict abortion laws also could hinder access to care. Some ob-gyns and gynecologists-in-training have reported leaving the Valley because of the restrictions.

The state could still do more with its existing programs, said James Gray, Texas government relations director at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. The cancer services program, for instance, can only serve 1 in 8 women who qualify, Gray said. “We’re always advocating for an increase in funding at the state level,” he said.

In the meantime, health experts and advocates are watching what changes Congress and the Trump administration will enact for Medicaid and the federal marketplace. If Medicaid funding or marketplace subsidies are cut and fewer people are eligible, many low-income women in the Valley could be affected.

***

On April 22, Maria and her family celebrated. Her biopsy had revealed she did not have cervical cancer. She was treated to a dinner with her favorite food, lasagna.

But Maria’s medical follow-up is not over. In four months she will need another pap smear to determine whether the LEEP successfully removed all abnormal tissues. The experience has changed how she thinks about such procedures.

“Now I fully understand both sides,” she said, referring to the patient and clinician experience, including how frightening and stressful it can be.

Her advice to other women in a similar position is to push forward and not give up.

“Once you get your bad results, you keep going because it’s better to know,” she said. “You can prevent it getting any worse.”

Daisy Yuhas is a science journalist and editor based in Austin.

This story is part of “Uninsured in America,” a project led by Public Health Watch that focuses on life in America’s health coverage gap and the 10 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

This story was co-published with the Puente News Collaborative. Puente News is a bilingual nonprofit newsroom, convener, and funder dedicated to high-quality, fact-based news and information from the U.S.-Mexico border.